An overview of rescissions...

...and the impact of the first Congressional-approved, Presidentially-requested rescission since the Clinton administration.

What are Congressional rescissions?

As laid out in the US Constitution, Congress controls the federal government’s spending, the power of the purse so to speak, while the executive branch administers the Congressionally-appointed funds. Should the executive branch disagree with Congress’s appropriations, the President can delay federal funding for a limited period of time through a process known as impoundment.

In 1974, Congress passed the Impoundment Control Act to keep the President from withholding monies for an extended period of time (at the time, Richard Nixon was refusing to spend Congressionally-appropriated funds). The ICA gave Congress oversight over Presidential impoundments, dictating that the President was obligated to spend appropriated funds, while also creating a legislative procedure to rescind said funds. Importantly, the president cannot legally impound federal funds indefinitely without direct approval from Congress. Both the President and Congress must approve rescissions.

Should the President wish to permanently cancel funding, the President can withhold funds and send a rescission request to Congress for permanent approval. The President can withhold funds for 45 days, but if Congress does not approve the rescission during this time period the executive branch must release these funds.

Because rescissions are subject to a time-limit on debate in the Senate (10 hours), rescission bills do not require 60 votes to proceed and can therefore pass with a simple majority. In today’s world of sharp partisan politics, where Republicans and Democrats have traded slim majorities in the Senate and generally refuse to support the other’s policies, this is an important exception.

How often has the ICA been invoked?

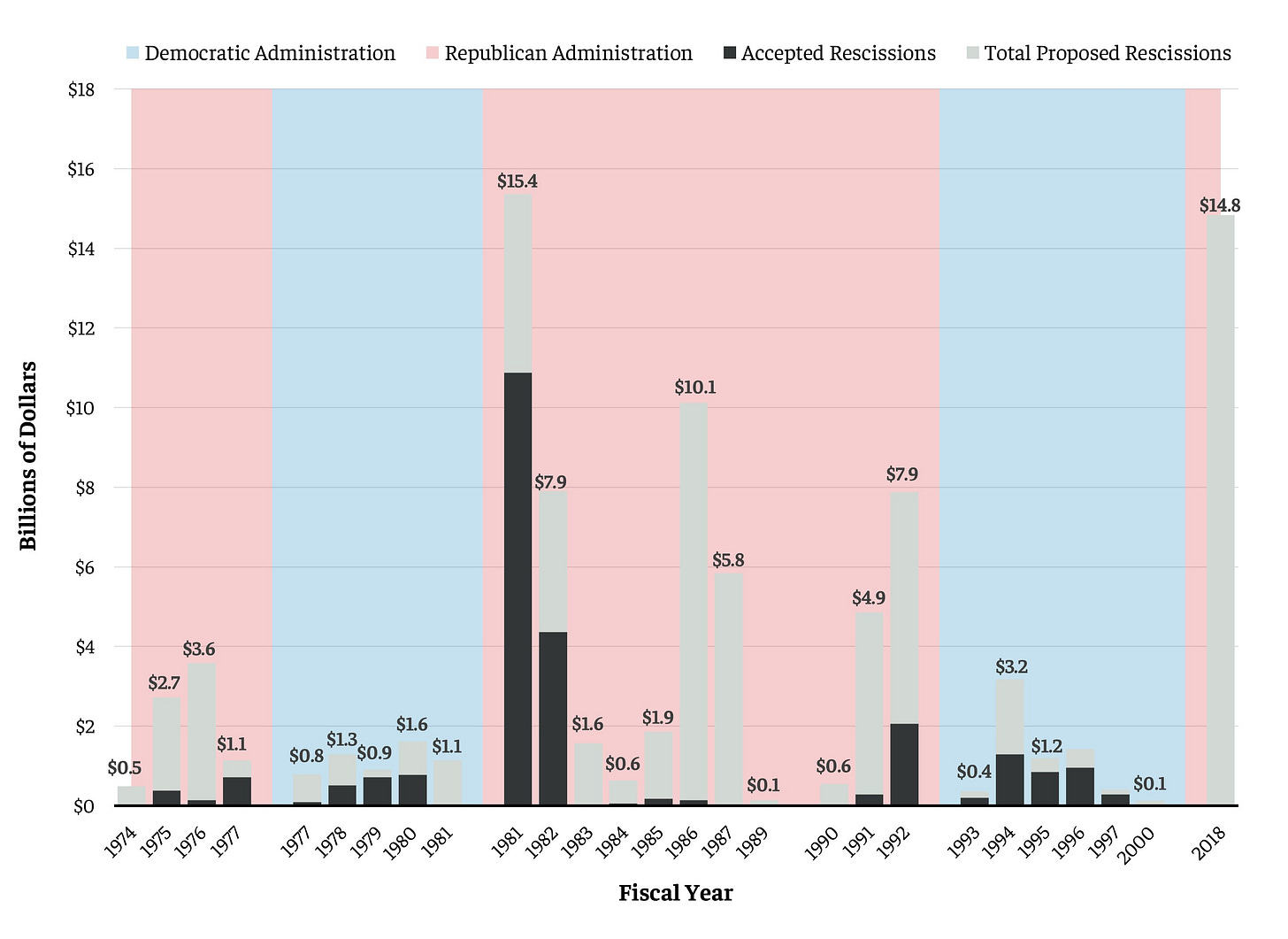

Since the ICA was enacted, the rescission power has gone through periods of popularity and obsolescence. Reagan liberally wielded the power, especially during his first term. In fact he submitted more rescission requests (133) during his first year in office than Carter had during his entire presidential term (122).

Rescission requests and approvals (in $) peaked in the early 80s as Reagan rolled back government spending.

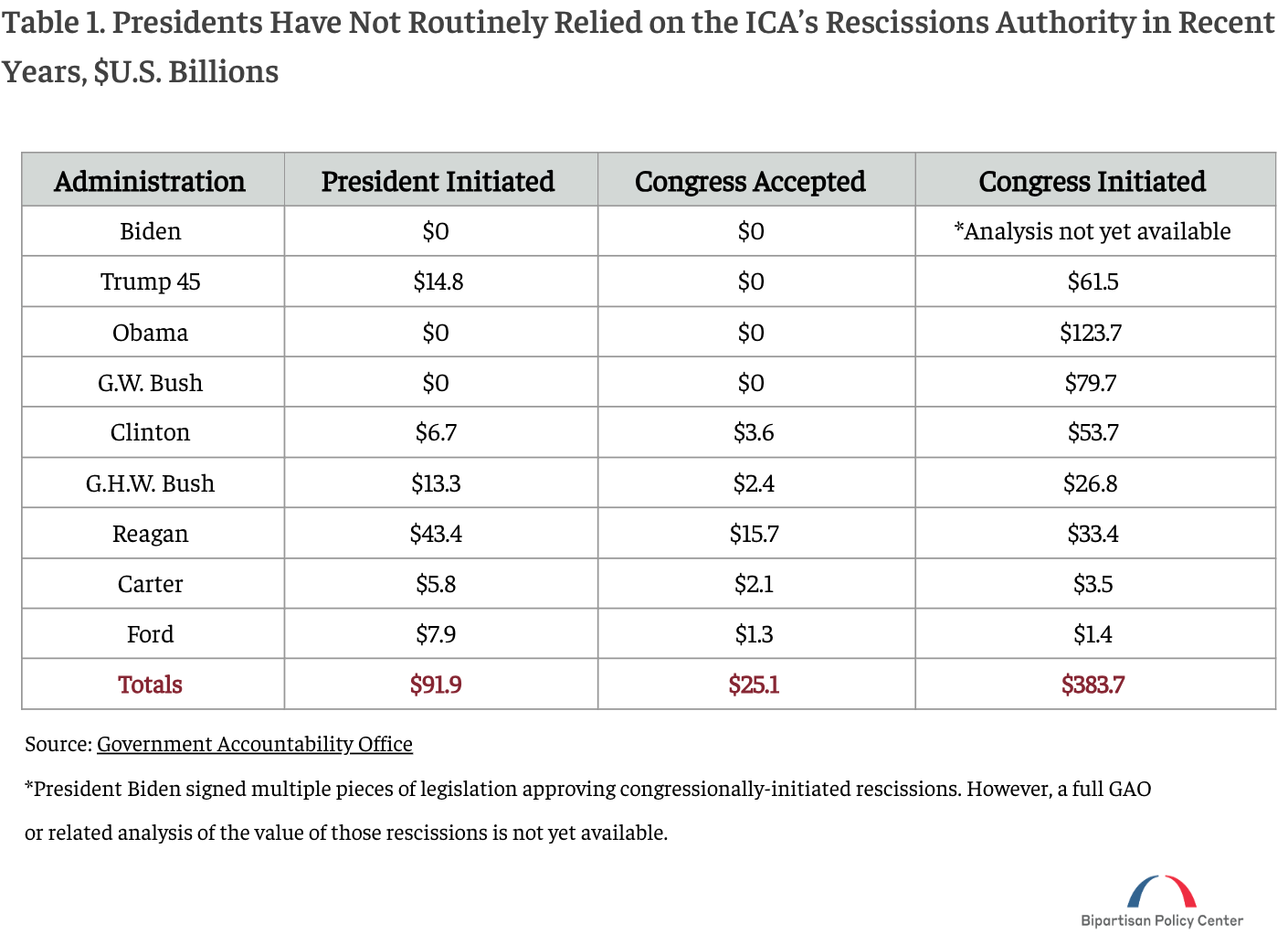

But after Reagan’s initial success utilizing the rescission process, Congress became increasingly reticent to approve requests. As you can see in the table below, over 60% of Congressional-approved rescissions between the Ford and Biden administrations took place during Reagan’s term in office.

George HW Bush and Clinton both had a few rescission packages approved during their terms in office, but nothing quite like Reagan. Under George W Bush, Obama and Biden, the rescission power was kept on ice. Trump proposed a some rescissions during his first term, but none of them were approved.

After peaking during the Reagan/Bush I years, presidential-initiated rescissions became increasingly less popular.

Instead, Congress has taken it upon itself to initiate its own rescission actions. This became a prominent feature of the Obama administration, where Congress launched nearly $124bn worth of rescission requests. It’s important to note though that most of these Congressionally-initiated rescission packages are simply reallocating unspent funds toward other priorities (e.g., emergency pandemic funding to offset other spending).

How much money are we talking here?

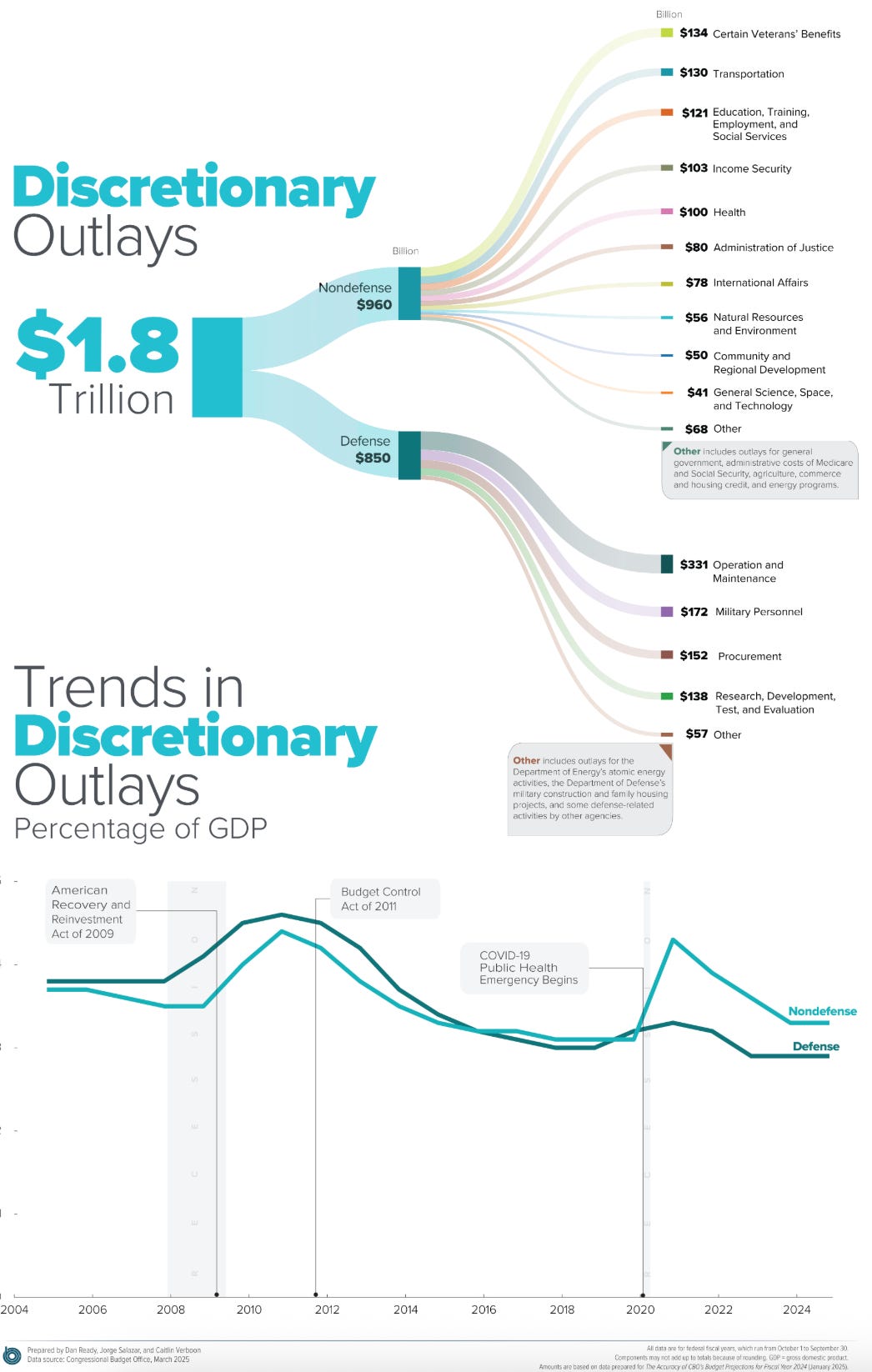

The federal budget consists of mandatory (60% of the budget in 2024), discretionary (26%) and interest outlays. Mandatory spending covers programs like Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security. Meanwhile discretionary spending is laid out under existing laws and formally approved by Congress and the President during the annual appropriations process. Slightly less than half of discretionary spending goes toward defense, the other half is devoted to various government programs like veterans’ benefits and federal infrastructure investments.

Rescissions can only be used on discretionary funds.

Excluding the pandemic era, discretionary spending has been on a downward trajectory.

Over the past fifty years, Presidents have initiated rescissions worth a total of $92bn, the overwhelming majority of which came during the Reagan and GW Bush years. Congress approved just $25bn, and none in the 21st century (that is, until earlier this summer).

As the acting Congressional Budget Office director noted during a 2006 hearing, the amount Presidents had proposed rescinding totaled “about one-half of 1 percent of the more than $15 trillion in total discretionary budget authority legislated [from 1976 through 2005].”

When it comes down to it, rescissions are relatively small potatoes compared to the US budget. But that doesn’t mean the programs impacted by rescissions are not important to everyday Americans and the global population.

What happened in July?

In a narrow vote supported by all but two Republicans in both the House and the Senate (and rejected by all present Democrats), Congress approved a $9bn rescission request made by the White House, the first time Congress has approved a Presidential-initiated rescission request since the Clinton administration.

The $9bn cuts relate predominantly to funding previously apportioned for foreign aid ($8bn), including $2.5bn in development assistance, $1.7bn in economic support for developing countries, $800mn in refugee support and $500mn intended for humanitarian assistance in disaster and conflict zones. To win over skeptical Republicans, $400mn for international AIDS relief (the Bush II-era program known as PEPFAR) and a few other food assistance programs originally included in the proposal were saved from the funding axe.

However, while the White House’s rescissions request proposed high-level cuts to areas like “global health programs” and “economic support fund”, the details of which programs are actually affected is still unclear — even to Congress. In explaining her vote against the request, Susan Collins, R-Maine, one of the two Republican Senators to vote against the bill, remarked that the bill “has a big problem — nobody really knows what program reductions are in it.”

Impact of cutting CPB funding

While the Trump administration has made no secret its desire to cut foreign aid, this rescission also takes aim at domestic targets. In addition to the $8bn in foreign aid cuts, the government struck $1.1bn from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), which represents the amount the organization was due to receive over the course of the next two budget years (~$550mn / year).

Established in 1967, the CPB provides Congressionally-appropriated funding for public news agencies like NPR and PBS. Republicans say public news broadcasters like NPR and PBS have been, in the words of Ted Cruz, “overtaken by partisan activists” and are left-wing propaganda machines. That being said, analysts who rate media bias and credibility, and the audiences of these public broadcasters, disagree.

A national poll conducted this summer found the US electorate was more trusting of public media than the media writ large.

Over two-thirds of those surveyed believe public media 1) is important for rural / underserved communities, 2) provides quality educational programming for kids and 3) over 60% feel it should remain free of charge.

Studies have shown public media, which does not have the same profit motive of most current media outlets, provides more in-depth reporting and is an important bulwark against misinformation and polarization.

NPR and PBS only get a small portion of their funding from the CPB, so programs like Sesame Street should be able to manage on reduced budgets, at least for a time (though in May, the Department of Education eliminated a $20mn grant used to fund children’s educational shows like Sesame Street, Clifford the Big Red Dog and Reading Rainbow).

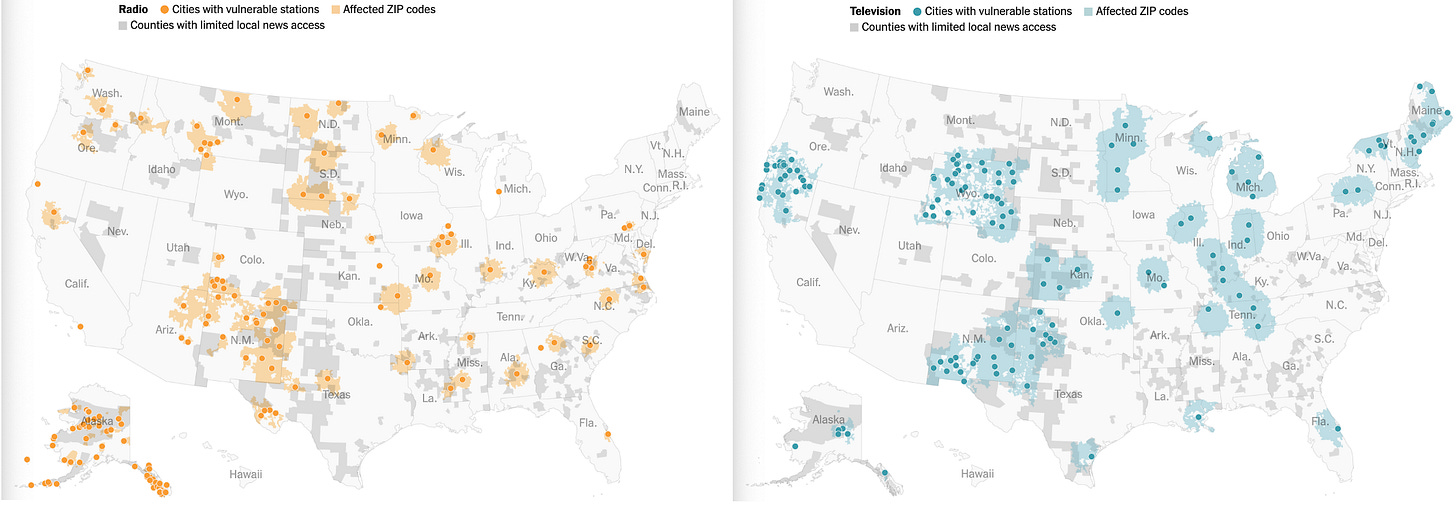

The real risk is to the local public stations that receive a larger percentage of their support from the federal government. According to the CPB itself, 70% of its annual funding goes toward local stations, some of whom rely on the CPB for half of their funding.

With Congress pulling the CPB’s funding, the advisory firm Public Media Company estimates that over 100 combined public TV and radio companies, largely concentrated in rural regions, could end up on the chopping block.

A map of vulnerable stations according to the analysis performed by Public Media Company.

A reported produced by NPR in 2011 found that cutting public broadcast funding would result in 30% of listeners nationwide losing access.

And NPR and PBS obtain funding through licensing fees paid by member stations and distribution revenue. These local stations pay NPR and PBS for the rights to broadcast NPR- and PBS-produced programming, but these funding cuts would eliminate this access and could precipitate a downward spiral where NPR and PBS customers go under, reducing the amount of money these national broadcasters bring in, thereby forcing NPR and PBS to cut-back.

In the face of local public stations potentially going under, at least 120,000 new donors have recently contributed ~$20mn in annual donations to try and stave off elimination. But $20mn in annual donations is just a fraction of the annual budget of $550mn that has been lost as a result of this rescission.

**********************************

After it success passing this first round of rescissions, the White House is reportedly considering another package for the fall, this time focused around the Department of Education.

One final point: As discuss above, the President cannot unilaterally cancel federal funding, any such action must be approved by Congress. An orderly following of this rescission process only works though if the government is operating effectively.

Last week, a federal appeals court ruled the Trump administration was free to continue impounding billions set aside for foreign aid, despite the White House not offering up any rescission order. The court did not rule on the constitutionality of the aid cuts. Instead, the court determined that the foreign aid organizations that relied on this money and had sued the government to release the funds did not have standing to do so. According to the court, only the Government Accountability Office (GAO, an independent watchdog of Congress) can challenge the President’s order to withhold funding.

If the President continues to impound funds without the GAO quickly challenging these efforts, the whole rescission process becomes moot, and Congress effectively loses its ability to control the government’s purse strings, further consolidating power in the hands of the executive, Trump administration.