Erdogan and the PKK

The end of the Kurdish militant group is another feather in the Turkish leader's cap.

Throughout Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s political career, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) has been a thorn in his side, stifling his regional ambitions for Turkey.

But after events of the past week, that all may be in the past. The PKK announced it would disband, declaring it was time to end its “armed struggle” with the Turkish government and “embrace the process of peace.”

This could be a major political breakthrough for Erdogan, who, if the reconciliation holds, will be able to trumpet his accomplishment of ending the multi-decadal conflict that has killed tens of thousands of people.

And it just might secure him another presidential term.

The PKK in Turkey

A bit of background

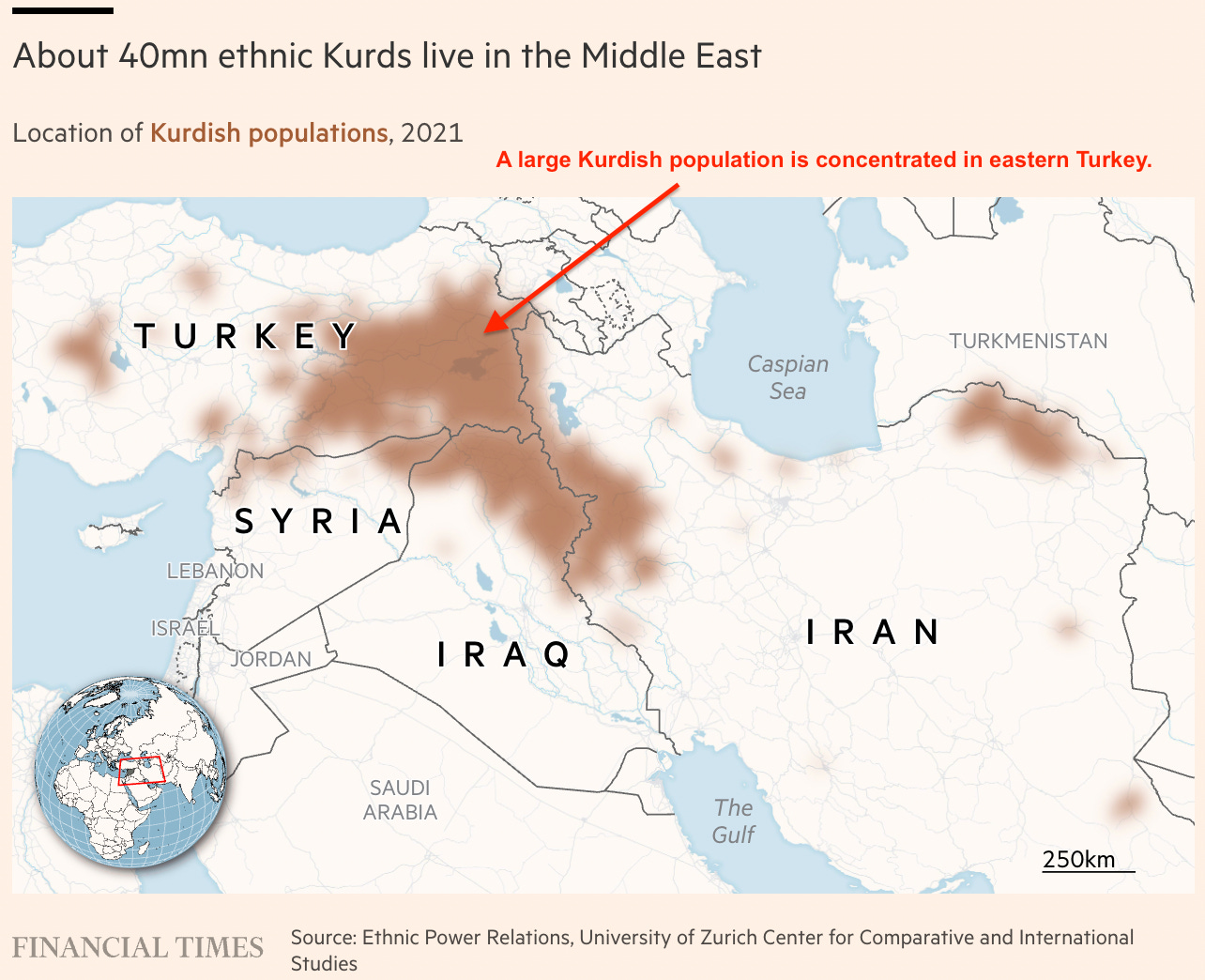

After decades of Kurdish suppression following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire post-World War I (at which time an independent Kurdish state was originally proposed but never fulfilled), Abdullah Öcalan founded the PKK in 1978 in a bid for Kurdish self-determination. The Kurdish population in Turkey is ~15mn (~20% of Turkey’s 85mn people) and has a sizable presence across the region in Iran, Iraq and Syria (for a total estimated population of around 30-45mn).

The vast majority of the Kurds live in the undesignated region of Kurdistan, located in modern-day Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran.

Since the group launched its violent insurgency in 1984, at least 40,000 people have been killed, mostly impacting the Kurdish side (though thankfully the violence in Turkey has subsided in the past decade). The PKK has long been designated a terrorist organization by the the Turkish government, as well as the US and Europe. It is estimated to have around 5,000 fighters mostly contained in the mountainous regions of Iraq, though around 60,000 supporters.

What did the PKK want?

While the group’s original goal was an independent Kurdish state (Kurdistan), its demands have moderated in recent years toward securing Kurdish rights within Turkey, like the acceptance of the Kurdish language in schools and decentralizing government to give Kurds more autonomy in the south-east of Turkey.

It also wants thousands of activists and political prisoners seized by the government to be set free. In the past decade, the Turkish government has invoked strong anti-terrorism laws to take a harsher stand against people thought to be sympathetic to the PKK. Hundreds of thousands of people lost their jobs, were arrested and subsequently convicted on terrorism-related charges. Since 2016, 170 Kurdish mayors have been removed from elected office, including eight members of the pro-Kurdish People’s Equality and Democracy Party (DEM, Turkey’s third largest political party) in the past year.

One recent example is the politician Selahattin Demirtas (nicknamed the “Kurdish Obama” when he ran for president in 2014 and finished third). Demirtas was arrested in 2016, ostensibly for making political speeches in support of peace talks between the PKK and the Turkish government, and has been behind bars ever since, despite a European Court of Human Rights appeal. After an initial four year prison term, additional charges were levied that extended his sentence to 42 years. Despite these efforts to suppress the Kurdish Demirtas, he collected over 4mn votes (> 8% of the vote cast) in the 2018 presidential election — while running from prison.

During the 2018 election, Demirtas performed exceptionally well in the south-east of Turkey, especially when you consider the fact he was imprisoned throughout the campaign.

Does this mean rapprochement? Is a Turkey/PKK agreement enough though to satisfy the Kurds?

As you may recall, talks between Erdogan allies and the Kurds had been ongoing for some time. The parties reached an initial breakthrough in February when the PKK’s founder/leader Abdullah Öcalan, imprisoned off the coast of Istanbul since 1999 on treason charges, called on the group to end its conflict with Turkey. “All groups must lay [down] their arms and the PKK must dissolve itself.”

But with the talks having been shrouded in secrecy, and the details not made public, there are still many questions we don’t know the answer to. How will the demobilizing process unfold? What will be the fate of PKK militants, and what if some do not wish to go quietly into the night? What rights did the Kurdish people receive and how will they be enforced (e.g., will new legislation be passed?)? What about the non-PKK groups in Turkey and across the Middle East that support the Kurdish movement (most notably the Syrian Democratic Forces and Iraqi Kurds) - how are they going to respond?

The wider implications

There is no denying that the past six months have been a major win for Erdogan.

Syria and the fall of Assad: While Turkey did not play a direct role, its support for the rebels certainly was a factor in allowing the group to develop and grow to the point where it could march on Damascus. A new regime in Syria loyal to Erdogan, coupled with the neutralization of the PKK, will give Ankara more leeway to project strength across the region.

Trump’s recent decision to lift Syrian sanctions is also an economic boon for Turkish businesses that could be inline to win contracts to help the ravaged country rebuild.

Kurds: The end of the PKK, not only ending a long, seemingly intractable, conflict, but also possibly securing Kurdish support to extend his presidential reign beyond 2028, when it is currently due to expire.

As the rising middle power: Offered to host peace talks between Russia/Ukraine after Putin proposed a direct discussion with Zelenskyy last weekend. Zelenskyy and Trump jumped at the chance to engage in in-person talks, but in the end Putin got cold feet and sent a junior delegation instead. While the talks were heavily downgraded, this is more because of Putin’s reticence than anything else. It is telling that all interested parties were willing to countenance Erdogan as the host, able to play with Russia, Ukraine and the US.

Ankara also reportedly played a role in brokering the ceasefire between India and Pakistan (though Erdogan’s close ties to Islamabad have annoyed many Indians who are now calling for a ‘boycott Turkey’ movement).

NATO: In addition to the aborted Russia/Ukraine talks, Turkey also hosted a NATO Foreign Ministers meeting in the seaside town of Antalya on Wednesday and Thursday.

Additionally, the appeal of Turkey’s large, formidable military, in the face of US retrenchment, could be key piece of leverage for Erdogan in securing more say within NATO.

Turkey has far and away the largest active European military in NATO.

Source: FT One sector of particular note is Turkey’s emerging strength in drone technology, which has played a pivotal role isolating in isolating PKK fighters in the Iraqi mountains. There are also unconfirmed reports that Pakistan used Turkish drones in the clash earlier this month with India. With Ukraine demonstrating just how vital drones can be in modern warfare, Turkey’s technical abilities in this space could be critical for NATO and Europe writ large as they build up defense capacity.

Opposition: Of course, amidst all of these recent moves, the arrest of Ekrem Imamoglu, the mayor of Istanbul and chief opposition figure viewed by many as the best chance yet to unseat Erdogan at the ballot box, should not be waved away. It is because all of these other moves are happening simultaneously though that the international democratic order has largely ignored this update.

Interestingly, even the imprisoned Imamoglu has said European governments should continue to support the Turkish defense industry.

Source: X

****************************

With Imamoglu theoretically off the electoral board, the opposition does not have the unity figure who can take on Erdogan. This is important because, as a reminder, Erdogan’s presidential term ends in 2028 and he is theoretically term-limited. That is, unless he gets enough support to amend the constitution. Could a peace with the PKK be a play by Erdogan to engender domestic Kurdish political support (from the DEM party), and for DEM to align with Erdogan’s legislative allies on this constitutional change?

Only time will tell.