Reflecting on Canada's failed carbon tax

The lesson? If you want something to succeed, make the result visible.

Before he became Canada’s prime minister, Mark Carney was a leading voice for climate action.

At COP26 in Glasgow in 2021, the former Bank of England governor announced the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, pulling together a group of asset managers, banks and investors the collectively managed trillions of dollars, to fight climate change. Even if commitments and pledges have not equated to action and results, the effort on Carney’s part was real, and certified his climate bonafides within the business community.

You would think that someone with that sort of background would be perfect to implement climate action at the policy level.

But when Carney replaced the flailing Justin Trudeau as Canada’s premier earlier this year, one of his first actions was not to double-down on Canada’s climate policies but in fact do the opposite.

Shortly after he was sworn into office in March, Carney signed a directive that lifted Canada’s 2019 consumer carbon tax. Carney described the decision as part and parcel with the government’s approach of ensuring Canadian “companies are competitive and the country moves forward.”

What is a carbon tax?

Generally speaking a carbon tax is exactly as the name implies, a tax to reflect the social cost of carbon embedded within products. Imposing a carbon tax increases the price of carbon-emitting goods and services.

Theoretically as products are taxed, their prices increase. In a world with options, consumers would migrate to less expensive products of a similar quality, sending a market signal to companies that they need to innovate and develop less carbon-intensive goods and services.

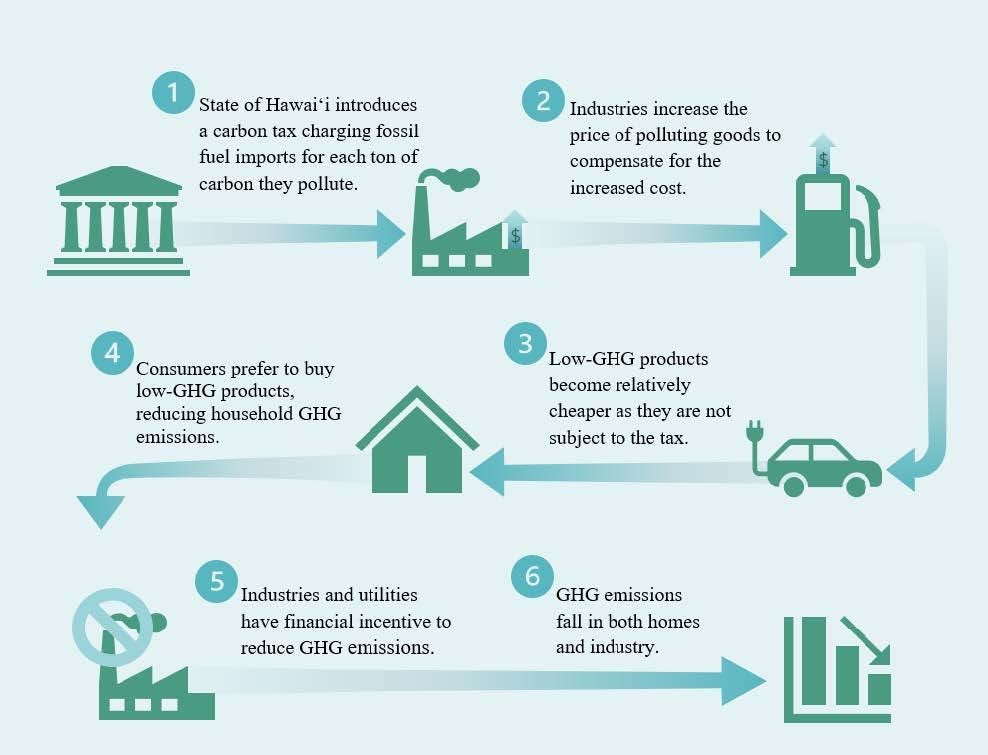

A nice little summary of a proposed carbon tax in the state of Hawai’i.

Economists love the idea of a carbon tax because it is a market-based approach that assumes participants will act in a rational fashion, leaving behind the carbon-emitting world of the past for a carbon-free future. At the same time, politicians do not like carbon taxes because, as their name implies, they are a tax and people simply don’t like taxes. Carbon taxes can also be largely regressive, since low-income families generally consume more energy-intensive goods, at a greater percentage of their budget, than wealthier households.

What was Canada’s carbon tax?

Back in 2019, during what was effectively the peak of the Green political movement, Trudeau introduced the first national carbon tax on fossil fuel consumption (e.g., on gasoline to fill up your car). The money collected through this tax was then returned to the Canadian people via quarterly rebates.

Why did Canada’s tax fail?

The carbon tax encountered the same problem as many other political initiatives: the negative impacts were front-and-center while the positives were hidden and poorly communicated.

Negative = visible: Every time consumers pay for gas at the station, they are hyper-aware of the price. As inflation raged in 2022, Canada’s opposition was able to fan the flames by equating the rising cost of gas to the steadily increasing carbon tax (which increased annually by 10-15 Canadian dollars).

The most recent carbon tax increase last April pushed the minimum tax on a liter of gas up from 14.3 Canadian cents to 17.6 Canadian cents (or in USD, $0.12 per liter of gas ($0.45 per gallon)). Per fill-up, that amounted to CAD11.26 in carbon taxes, and was due to increase to CAD34.82 by 2030.

Positive = hidden: Despite the reality that the average family received more money in carbon rebates than they paid in carbon taxes, the uneven visibility of the impact disproportionally weakened the carbon tax.

The rebates were not well publicized. Initially they appeared as discounts on annual tax statements and then revised to arrive as direct payments to individual bank accounts. However, the payments were not clearly labeled in bank accounts (until the government passed a law last year requiring banks to identify the direct deposit as a “Canada Carbon Rebate”) and were only seen by the recipient if they checked their bank transactions on a regular basis.

What can we learn from this experience and apply going forward?

Ultimately, the carbon tax was unpopular and Carney made the politically expedient move to reset the field and win votes (and ultimately get elected as prime minister in April).

But that doesn’t have to be the end of the story.

The first lesson is the simplest: accentuate the positives! Make it loud and clear that the money being collected through the carbon taxes is being returned, and make those returns as visible as possible. Put paper checks in the mail and give the recipients a chance to really feel their good fortune.

In a bit of a curve ball, a recent study found that residents of both advanced and developing economies were more enthusiastic about using the income from carbon taxes on infrastructure projects, rather than returned as a direct cash. In other words, people support investments in the future, and are willing to pay taxes to finance them. If this is the route pursued, the outcome must be visible and readily promoted as the result of monies from a carbon tax.

What about a carbon ‘tariff’?

Finally, you may think Republicans, as the party against taxes, would be against a carbon tax. Generally speaking, you are correct. But what if you rebrand it as a carbon ‘tariff’??? If applied to only imports into the US, that is essentially what a carbon tax is, a tariff. This is exactly what a couple of Senators recently did when they introduced revised legislation in April that would impose a tax on the carbon emissions of certain imports.

While this would do little to address America’s own domestic emissions, it would require foreign exporters to do a bit of innovating if they wanted to avoid contributing money to the US government. A recent paper found that the proposed carbon ‘tariff’ would produce as much as $40bn a year in federal income (paid largely on imports from Canada and Mexico). Considering the US government has collected $3.5tn in revenue thus far during fiscal year 2025 (since October 2024), $40bn is a mere drop in the bucket. But it’s better than nothing, and is being applied in a more meaningful (albeit still discriminatory) manner than Trump’s Liberation Day tariffs.

************************

At the end of the day, for policies and politicians to be successful, voters need to see and feel the results. Whether that comes in the form of paper checks or real infrastructure, what matters is the end product, not platitudes.

Does this create a duration problem, between short-term political aspirations vs. long-term development goals? Yes it does — but that is where political parties need to demonstrate an ideological commitment and a willingness to stick to the path, while also building in small, real wins along the way.

The carbon tax in Canada may have failed, but if governments so choose, they can learn from this experience and design better policy that can last the long haul.

Thanks for this very good piece.