On June 8, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA or National Weather Service) announced that “El Niño conditions are present and are expected to gradually strengthen into the Northern Hemisphere winter 2023-24.”

NOAA officially declares an El Niño event when the 3-month average sea-surface temperature is greater than ~1°F in the east-central equatorial Pacific (the black box in the chart above).

The nifty little flow chart below documents the process for determining if we have met El Niño conditions.

On the 4th of July, the World Meteorological Organization reiterated NOAA’s announcement, saying El Niño conditions had developed for the first time in seven years and setting the stage for a likely (90% certainty) El Niño event.

El Niño has been described as the “trunk of the tree of climate variability” and is the most important source of year-to-year climate variation. El Niño typically develops over the summer and exhibits its strongest impact in the Northern Hemisphere during winter. Scientists are predicting this El Niño has a 56% chance of peaking as a “Strong” event, and an 84% chance of at least a moderate peak.

As the chart lays out below, we have experienced 26 El Niños since the early 1950s. Only three have been “Very Strong”, which is defined as ONI greater than 2C. Most have been Weak or Moderate. So a “Strong”, not to mention a “Very Strong”, El Niño would be a big deal.

What is El Niño?

In the 17th century, fishermen in South America noticed that the water off the coast would occasionally get warmer around Christmastime. Deriving its name from the Spanish word for “little boy” (or the Christ child for Christians around the holidays), El Niño is half of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO), with La Niña the other half (and little sister). The ENSO cycle is the year-to-year variation in the equatorial Pacific Ocean’s surface temperature and the air pressure above it. El Niño and La Niña represent the cycle’s polar opposites.

When the ENSO cycle is in a warming phase, the surface temperature rises and a period of El Niño occurs. Contrarily, when there is a cooling of the surface temperatures, La Niña happens. However, when temperatures are at or near average, neither develops and we are at a steady state (of ENSO-neutral). Typically these ENSO-neutral periods are a transition from El Niño to La Niña (or vice versa).

There is an air pressure component that is also considered. Scientists measure the difference in air pressure between the western (Darwin, Australia) and eastern (Tahiti) parts of the equatorial Pacific, more than 5,000 miles apart. When the pressure is lower than normal in Tahiti and higher than normal in Darwin, conditions favor the development of El Niño. When the opposite occurs, La Niña may develop.

In a normal year, the trade winds move warm surface water away from the Western South American coast westward towards Australia. This allows colder, nutrient-rich water to come up to the surface along the South American coast. This phenomenon of pushing nutrient-rich water up from deeper in the ocean is known as upwelling, and is crucial for enabling life in the sea.

When El Niño conditions are present, the trade winds slow down and warm water reverses course, heading east towards South America. The warm water movement concurrently moves rain and evaporation, resulting in a drier ASEAN and Australia. This also removes the temperature gradient required for cold water to upwell from the depths of the ocean. That means the tropics and subtropics are warmer than normal, causing average global temperatures to rise.

What will be the impact?

Meteorological impact

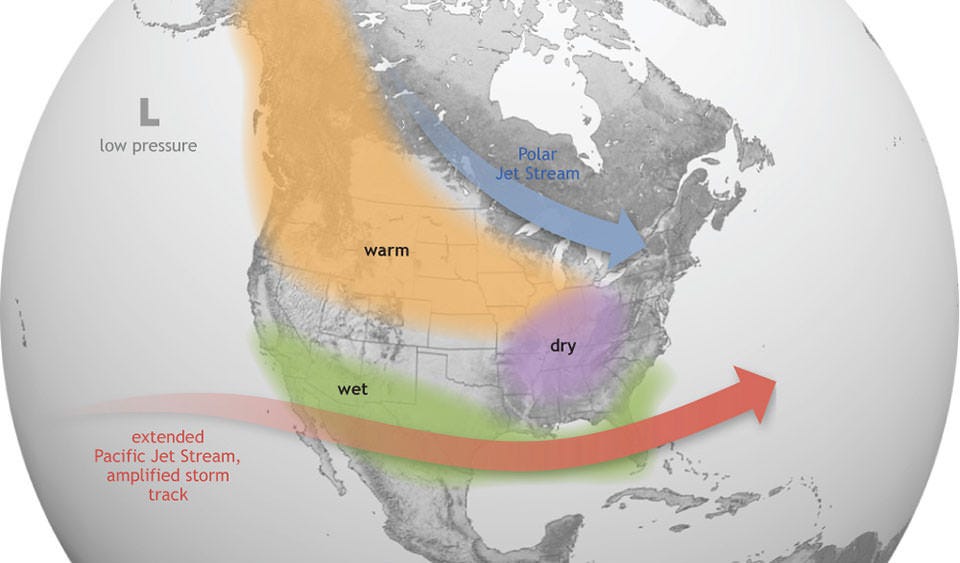

Generally speaking, wind and rainfall patterns will change. The warm waters near South America cause the Pacific jet stream to move south of its natural position, which tends to bring wetter conditions to the southern US and warm/dry weather to Canada and the northern states.

The National Weather Service has predicted that much of the US this summer has an above average chance of temperatures being higher than average. This is especially true along the East Coast, flowing towards the southern states and then along the Rocky Mountains up to Canada. As we have seen, this prediction made in the middle of June has already come to fruition.

It’s important to note that scientists are not sure when El Niño will peak and how it generally will play out. Richard Allan, professor of climate science at the University of Reading, told the Financial Times in June that “it’s too early to say how the current El Niño storyline will unfold. But if it does unleash its full power in 2024 then it’s very likely that yet another record global temperature will be breached.”

As the below chart produced by Columbia University shows, aside from the US impact, there are pockets of increased rainfall in southern South America and the Horn of Africa. Conversely, there is a risk of drought in parts of Brazil and northern South America, ASEAN and Australia.

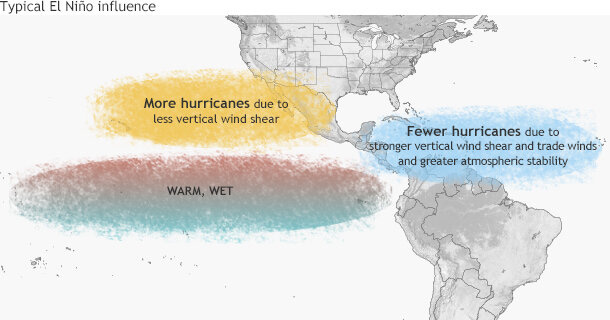

Another important impact El Niño could have is on hurricane season. Because of the shifts in the wind shear (the change in wind speed/direction in the area 5,000 - 35,000 ft above the ground), El Niño’s tend to result in more intense hurricanes in the central / eastern Pacific, affecting Mexico, and softens those in the Atlantic.

NOAA has given the 2023 hurricane season a 40% chance of being ‘near-normal.’ At the same time, there is a 30% chance either way of it being ‘above-’ or ‘below-,’ though they expect fewer named storms this year than in the especially busy 2020 and 2021 seasons.

In a post-pandemic world, we are all (or at least we all should be) more conscious about the risk of infectious disease. Previous El Niños have been linked to creating the ecological conditions that lead to disease outbreaks in regions of the world (like Brazil, Southeast Asia, Tanzania and the western US) affected by shifts in temperature and rainfall. For example, in Brazil and Southeast Asia scientists found El Niño’s conditions contributed to increased dengue and chikungunya fever outbreaks. Scientists have also found a strong association with El Niño and malaria and cholera outbreaks in parts of Asia and South America.

Economic impact

There are very few parts of the world that are not impacted economically by El Niño. A recent scientific study found that El Niño resulted in as much as five years of slower economic growth. Some of the key findings were:

Global economic losses of $4.1tn and 5.7tn, respectively, in the five years after the 1982-82 and 1997-98 El Niños.

5 years on, in 1988 and 2003, US GDP was 3% lower than what it would have otherwise been had El Niño not occurred.

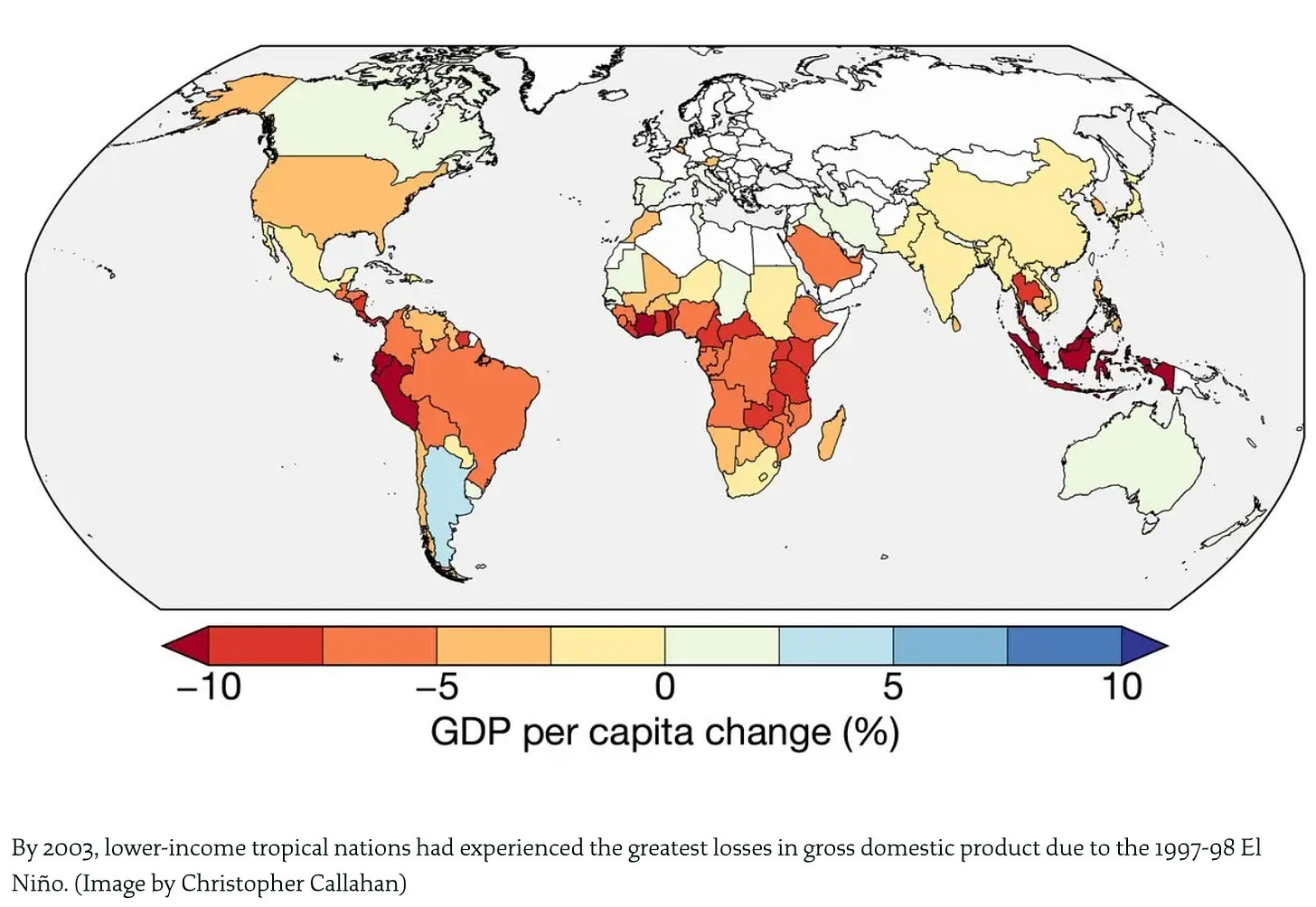

El Niño also exacerbates economic inequality, disproportionally hitting the least well-off populations the hardest. In 2003, the GDP of coastal nations like Peru and Indonesia was lower by more than 10%.

The 2023 El Niño alone could result in the global economy losing $3tn by 2029.

As the map below outlines, GDP per capita dropped across much of South America, ASEAN and southern Africa, all developing regions, as a result of the 1997-98 El Niño. The direct economic impact in Europe and other developed countries outside of the US was minimal, though with inflation still acting as a bugaboo for much of the world economy, shocks to commodity prices could extend this period of high prices.

So what causes these economies to weaken?

Indonesia and south-east Asia are key producers of commodities like palm oil, rice and coffee beans. El Niño brings the threat of prolonged drought to the region, and water supply would take a hit and agricultural output would fall. While the Malaysian Palm Oil Board had announced in May that El Niño might result in reducing palm oil output by around 3mn tons in 2023, the chairman recently announced that El Niño would not impact palm oil yields in the second half of 2023. So that’s a bit of good news.

Similar warnings have been issued for other home-grown commodities:

Vietnam, the largest producer of robusta coffee beans, could see a drop in coffee production by 10-20%

Thailand’s Office of the Cane and Sugar Board, the world’s third largest sugar producer, projects sugar cane production could drop from 94mn tons in 2022 down to 70-80mn tons this year.

Thailand’s rice yields (of which it is the second-biggest global supplier) could also fall.

The futures price of El Niño-impacted commodities like coffee, sugar and cocoa have already started ticking up. And as you can see below, the price of robusta coffee is now hitting 15-year highs.

A drought in this region would also impact hydropower output. With these countries looking to diversify their economies into manufacturing production (especially in the wake of Western nations de-risking from China), reduced hydropower could result in power outages and potentially slow growth. Vietnam’s state electricity utility company (Electricity Vietnam) has already called this a “national electricity-saving movement,” asking government and households to cut-back while imploring businesses to limit usage during peak hours.

Extended periods of drought could also exacerbate fires in Indonesia. With El Niño causing parts of Indonesia to see no rain or just 30% of the typical amount, the risk of damaging fires will rise. During the moderate El Niño in 2019, the country experienced fires worth an estimated $5.2bn.

From a US-perspective, El Niño brings more rain to the western states. While there have been some recent exceptions, a stronger El Niño will likely result in more precipitation for California and the southwest US. This is important because the vast majority (98%) of California homeowners lack flood insurance. Couple this with the insurance market fleeing California, and this could spell trouble for Californians.

***************

As the chart below shows, we fluctuate between El Niño and La Niña periods a few times a decade.

Since 2020, we had been experiencing an extended period of La Niña. This is important because La Niña’s cooling effect likely trapped more heat in the oceans and helped reduce climate change-related warming.

What’s remarkable is that even though we were experiencing La Niña, 2022 still registered as the hottest year on record for 28 countries. El Niño’s warming effects “working” with climate change means the coming years could be unprecedented (and not in a good way).

The World Meteorological Organization is predicting there is a 66% chance that global temperatures exceed 1.5C for at least one year between 2023 and 2027. This will be a temporary occurrence while we are experiencing El Niño; scientists say there is only a 32% chance that the average 2023-2027 temperature will be greater than 1.5C. But just the same, that doesn’t mean the impacts won’t be material.

No matter how you slice it, El Niño is a shift from the past few years. This will have ecological and economic impacts no matter where you live.

Bringing this full circle

And now, a brief trip down memory lane.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nuance Matters to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.