The problem with carbon offsets, part 1

Carbon offsets are generally low quality and thus do not help stem the tide of climate change.

Last week I wrote about carbon markets, both the government-run credit markets and the voluntary offset markets. If you missed it, refer to the link below.

The post ended with the view that offsets are a generally underwhelming product that don’t offer much substantive benefit. In this article, I talk about why this is the case. Since there are a lot of reasons why offsets don’t really work, I have broken this into two separate posts.

*************

Europe’s regulated carbon credit market is the Carbon Development Mechanism (CDM). The CDM subsidized thousands of clean energy projects which, in a vacuum, is great. However, this market has also subsidized coal plants in India and China, with European companies purchasing carbon credits because the coal plants were “more efficient” than the plants could have been. The CDM has been associated with quality issues to such an extent that ProPublica cited a 2016 EU report finding that 85% of the CDM-generated credits had a “low likelihood” of creating real impacts.

The main issues

So why are these credits, and offsets more generally, of such poor quality?

Leakage

As we are all aware, climate impacts are global. Decarbonizing in one location doesn’t mean you eliminate the risk of a disaster. In a similar way, consideration needs to be given to how carbon credits shift emissions off-site. The risk is that reducing emissions in one location will cause emissions to increase in another. This is known as leakage.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defined leakage as “the unanticipated increase or decrease in greenhouse gas benefits outside of the project’s accounting boundary as a result of the project activities.” In this context, leakage does not mean physical carbon leaking from a site, but rather the secondary impacts caused by decisions made.

Deforestation is a good example of how leakage can occur in real life. Say a company promises to protect a square mile of forest and create offsets for these avoided emissions. However, that same company decides to just move operations to an adjacent square mile, implementing the same deforestation plan, and negating the impact of the carbon offsets (known as activity shifting). Logging can take place anywhere there is forestry, so if it is forbidden on one site, the loggers can easily move to another site. Less available land to log might also increase the price marginally, which could reduce overall levels of logging, but the final demand will likely still need to be met. This leads to market-shifting leakage, where the changes in supply / demand induce activity that cancels out the impact of the project generating carbon offsets.

A 2022 study of California’s offsets related to forest preservation determined that “[California’s] protocol’s use of lenient accounting methods” meant that actual leakage rates were 4x higher than what the protocol assumed. In turn, the paper concluded that by not properly accounting for leakage, California’s carbon offsetting process may actually be increasing emissions.

Countries also risk increasing leakage when they tighten their emission caps and decrease the number of available carbon credits. For example, companies operating in Europe where the EU Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) operates may shift production overseas to a market not covered by an ETS. While emissions in Europe may decrease, global emissions stay the same, and the credits are just greenwashing - presenting the appearance of doing good while in reality just shifting emissions from one location to another.

Over-crediting

In order to determine the impact of an offset, you have to establish an indisputable baseline.

A baseline represents the scenario that was most likely to have occurred without the offset project taking place - and thus is the scenario against which the offset project’s impact is measured. However, a baseline is inherently counterfactual; after a project is implemented the baseline cannot be observed or measured.

Let’s use deforestation again as our example. The math starts with an estimated baseline, a guess at what emissions from deforestation would look like without offsets. However, it is easy to game the system by nudging the numbers toward the bleakest alternative reality. When project developers have the flexibility to determine a baseline, they have the financial incentive to choose the baseline option that generates the most credits. The more deforestation you anticipate, the more credits you generate, and the more money you stand to make.

For example, the Guardian’s report on Verra, the carbon offset certification program, cited a 2022 University of Cambridge study that found the threat to forests was overstated by ~400% for each project. By overstating the threat, the impact of offsets is inflated, making the carbon offsets produced less impactful.

Moving away from nature-based solutions, another example of over-crediting has been found in replacing dirty cookstoves that are used by close to 3bn people worldwide with more efficient ones. A 2023 study found that this cookstove replacement accounted for more than 10% of projects on the voluntary carbon market. However, in an analysis of 36 projects, they determined the average projected generated ~6x more credits than the estimated climate benefit, meaning each credit is a lot less meaningful than advertised.

Even under ideal circumstances, determining how successful an individual project is at sequestering carbon cannot be easily measured. Having good data is essential for reducing baseline uncertainty, but even if you have information on things like initial carbon stocks, benchmarks and net present values that are reasonably predictive, it all comes back to an educated estimate that cannot be proven.

Additionality

In 2020, Bloomberg did extensive reporting around firms like JPMorgan, Disney and BlackRock working with the Nature Conservancy. The Nature Conservancy sold offsets to these companies ostensibly to fund the preservation of forestland in the Northeast US. The thinking was that these companies were paying the Nature Conservancy to prevent the forestland from being torn down. However, Bloomberg’s reporting found that this forestland was already well protected by the state and the Nature Conservancy itself had no hand in actually saving the forests.

This is an example of offset projects not providing additionality. Additionality means that the carbon efficiency gains are made only if the savings would not have happened without the offset project. Danny Cullenward, a Stanford professor, notes that “for the credits to be real, the payment [for the offset] needs to induce the environmental benefit…[if there was never any intention of cutting down trees] they’re engaged in the business of creating fake carbon offsets.”

For most carbon offsets, this is a very high bar to reach. Another Bloomberg investigation in 2022 examined over 215,000 carbon offset transactions focused on renewable energy projects. They found that since the cost of renewables has dropped so much, it is a virtual certainty that these projects would have been given the green light even without the offset revenue. A similar analysis by the European Commission over the CDM in 2016 came to the same conclusion. In fact, the top offset certifiers, Verra and Gold Standard, stopped issuing offsets for grid-connected renewable projects in 2019 except in the poorest countries.

Durability of nature-based solutions

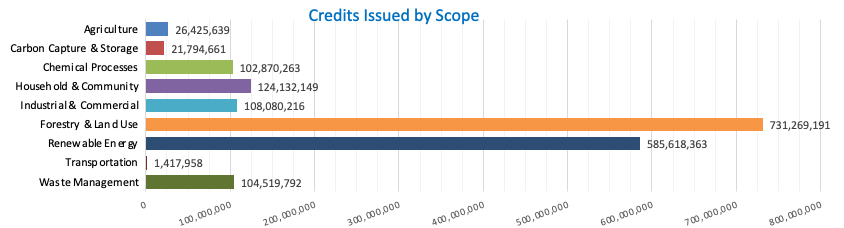

Nature-based solutions have grown increasingly popular, accounting for 45% of the credits generated in the voluntary carbon markets last year. Nature-based solutions generate credits through programs like (1) forest conservation or restoration to keep sequestered carbon in trees, and (2) changing agricultural practices to reduce emissions or improve carbon storage techniques.

Beyond the issues already discussed above though, there are a few problems with planting trees as your offset strategy. For one, trees store the carbon - it doesn’t magically evaporate into thin air. So when trees are destroyed, either by deforestation or forest fires, the tree’s captured carbon is released back into the atmosphere. An example is the 2021 forest fires in the Pacific Northwest which burned down forests that were funded by offsets purchased by companies, including Microsoft. A fundamental tenet of offsets is that they offer permanent benefits. Unfortunately, trees do not guarantee a permanent carbon sink.

Additionally, when you plant a tree, it doesn’t all of a sudden absorb all of the carbon in the atmosphere. Trees take years to fully grow and slowly capture carbon over time. Unfortunately, time is something we do not have at the moment. The carbon is in the air and a slow unwinding is not going to be sufficient.

In 2023, concerns over the quality of nature-based solutions, coupled with tighter macroeconomic conditions over the past year and increased scrutiny into company claims of net-zero, means that the price for nature-based offsets has plummeted.

Carbon capture and removal

A more permanent alternative to nature-based solutions is direct air capture. Direct air capture uses the most advanced technology available to suck carbon from the atmosphere and store it permanently underground.

The tech firm Stripe recently paid $775/ton to Climeworks, a Swiss company that uses renewable energy to capture CO2 from the air and store it in underground rock formations. In this example, not only is there an assurance of additionality - the CO2 would not have been captured without Stripe paying Climeworks - but the reduction is permanently stored in the underground rocks.

Obviously, $775/ton is a lot of money - especially when compared to the peanuts that nature-based solutions currently cost. Climeworks hopes to bring the cost down to $100-200/ton, but this technology has not yet been proven at scale. And since this process is currently so expensive, removal credits today make up just 3% of the voluntary carbon market.

Long-term contracts to scale up this technology are essential to get companies like Climeworks to invest, and eventually reduce the cost. However, even Climeworks knows that carbon capture and storage is not something that will happen overnight. The company’s co-founder and CEO recently noted that Climeworks could continue to see its price set at as high as $300/ton in 2050.

*****

In my next post, I will cover more nuanced issues like double-counting and the climate justice aspect of carbon offsets.

Interesting stuff. No wonder I never understood how carbon offsets worked ... because they don't!