On Monday morning (May 12), the US and China announced a pause on the triple-digit tariffs each had been put in place around Liberation Day (April 2). Chinese exports to the US though are still subject to a minimum 30% tariff (the 10% floor for all imports + 20% specific to China’s roll in the fentanyl trade) while China will tax US exports at 10%.

Despite the still high trade barriers in place, markets reacted to the news with glee.

Of course this is only a temporary reprieve. The two global powers now have 90-days to negotiate an actual deal (or the appearance of one, like the UK trade deal that doesn’t really do much).

One sector both the US and China might want to concentrate on is rare earth elements.

Rare earths and critical minerals are not interchangeable terms.

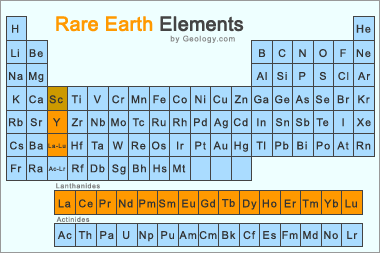

This is a post about rare earths, NOT critical minerals. ‘Critical minerals’ is an all-inclusive term which includes elements you have probably heard of like nickel, lithium, copper and cobalt (and others). Rare earths are also critical minerals, but are a specific list of 16 or 17 (depending on who you ask) elements found on the periodic table that are not as well-known.

The rare earth elements are the 15 lanthanide series elements, plus yttrium (in orange below). Scandium is found in most rare earth element deposits and is sometimes classified as a rare earth element.

Here is a simple rule: all rare earths are critical minerals, but not all critical minerals are rare earths.

It’s like the square / parallelogram lesson from elementary school. All squares are parallelograms, but not all parallelograms are squares.

Parallelograms have four sides, with opposite sides being parallel to each other. Squares are parallelograms with four sides of equal length and 90 degree angles.

What are rare earths used for?

In 2023, the global rare earths sector was worth just ~$7.5bn, making it a relatively minor market compared to other critical minerals like lithium (valued at $22bn in 2023). Part of the reason for this disparity is that, contrary what the name implies, rare earths are not actually that rare. As one scientist noted, thulium, the rarest of the rare earths, is 125 times more common than gold!

The circle of life for rare earths: From a deposit in a mine —> mined compound —> separated into refined elements.

Rare earths are commonly found in the Earth’s crust, but are so widely-dispersed at such low concentrations that it is difficult to efficiently mine them at a low cost and in an environmentally sustainable manner. Mining and then individually separating and purifying each rare earth is a time-consuming process of trial and error that can take years to master.

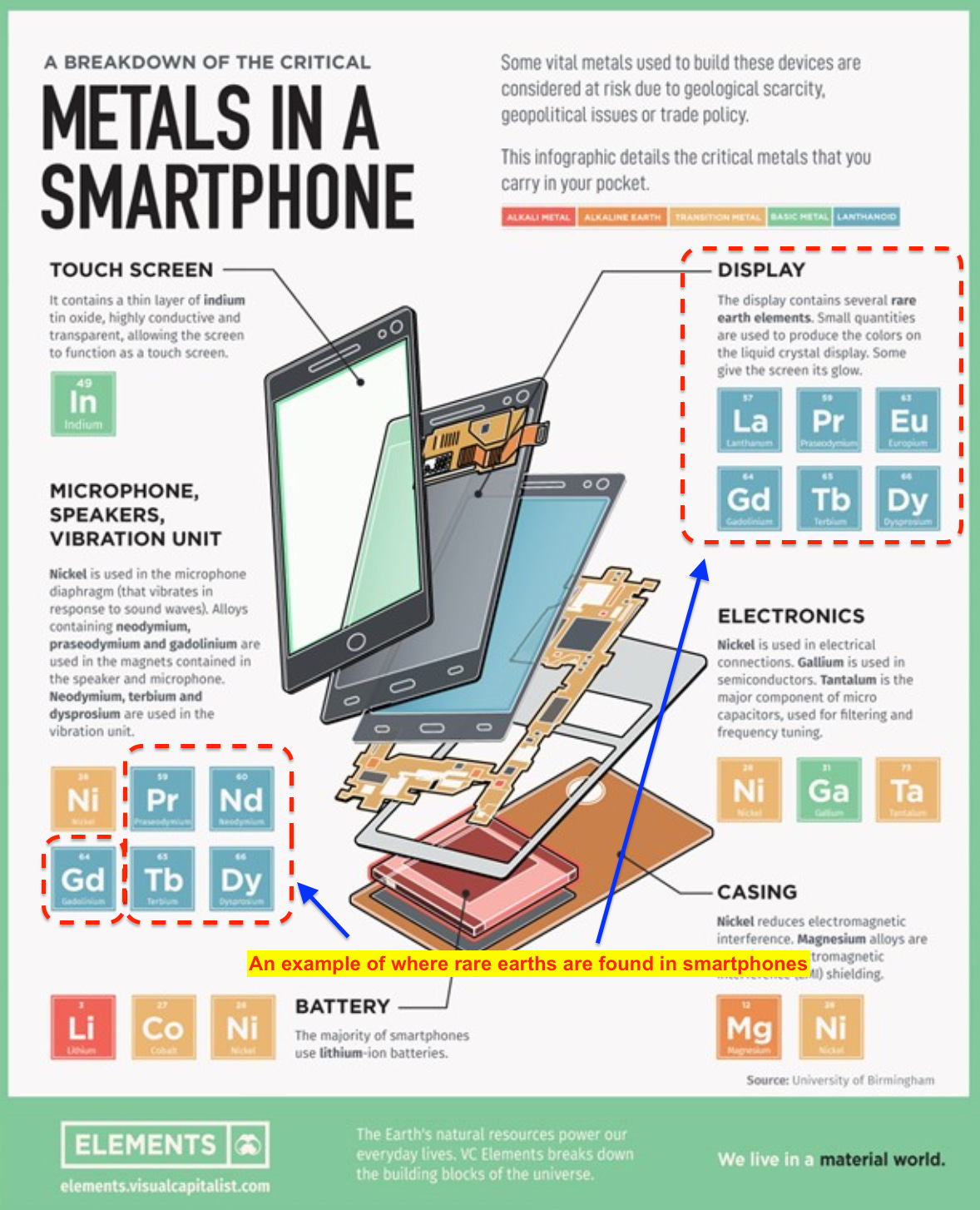

Rare earths are found in a variety of devices

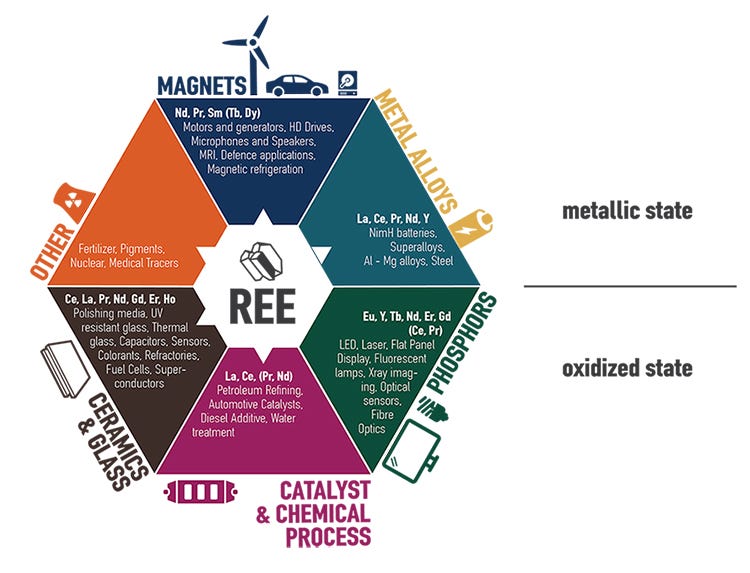

Rare earths are used across a broad set of applications, including magnets, batteries, chips and nuclear reactors. They are also widely used in US defense technology, including missiles, drones, jet engines and naval battle ships. Because of their importance within the battery value chain, the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts demand for rare earths within the clean tech industry will increase 6x from 2021 to 2040

Example of rare earths in a smart phone

China’s evolving rare earth monopoly

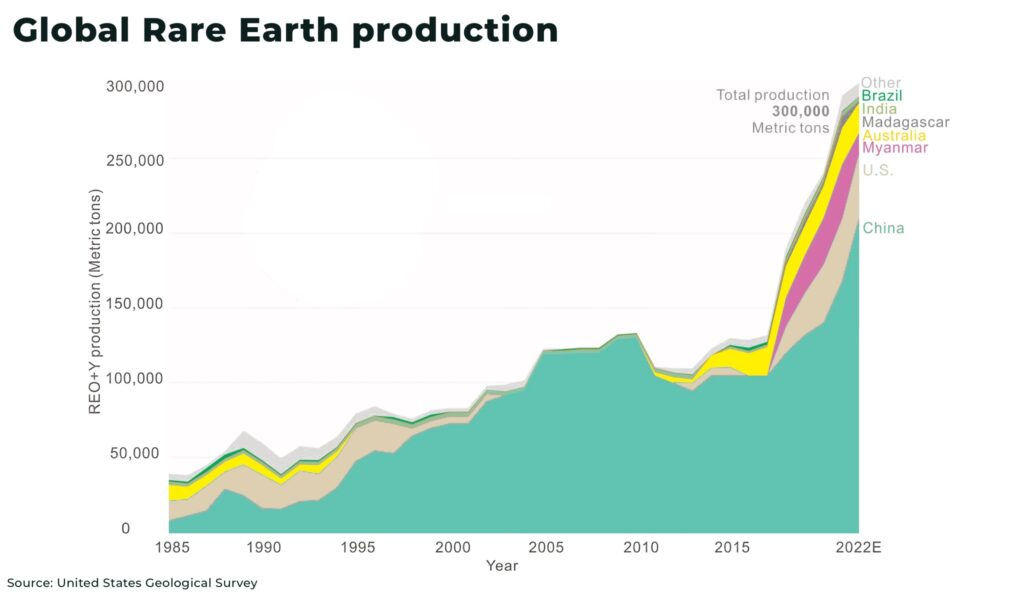

Back in the early 90s, the US was actually responsible for 33% of global production, second only to China’s 38% market share.

Since the mid-90s, China has dominated the rare earths sector.

But in the late 90s and 2000s, US production collapsed. America’s primary rare earth mine, Mountain Pass, shutdown in 2002 for a decade over environmental concerns. Meanwhile China continued to invest, handing Beijing a veritable rare earths monopoly.

The US’s Mountain Pass mine, which reopened in 2012, accounts for ~15% of global rare earths production. However, this pales in comparison to China’s dominance throughout the value chain of processing, refining and manufacturing rare earth products.

And this is the case across all rare earth elements — China has the dominant position. In fact, in 2024 the US itself extracted rare earths worth $260mn, but sends a lot of them to China for processing.

Last year, China dominated rare earth refinement, while the US and its allies barely registered an industry presence.

Decades of state-backed funding and a lack of regulatory hurdles allowed Chinese companies to ignore periods of low commodity prices to dominate the sector. Chinese firms would flood the market while ignoring standard supply/demand economics, driving down the price and undermining the commercial prospects of western companies, who typically rely on higher prices to incentivize production.

The price of rare earths spiked during the energy crisis of 2022 but quickly fell again, stabilizing at levels a bit higher than pre-2022.

However, as mining expanded across China, some of it unregulated and illegal, Beijing is now dealing with environmental damage, including water and soil pollution (which is largely why it ended up so concentrated in China in the first place). In 2021, the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) environmental agency even went so far as to shutdown some rare earth factories because of the ongoing environmental harm.

It is important to note that, when it comes to rare earths, China is not wholly self-sufficient. It has increasingly migrated extraction to Myanmar’s (largely unregulated) mines along their shared border.

***********************

What is the US doing to catch up to China’s position in the market? Could the US build its own domestic supply chain, or perhaps collaborate with allies?

We’ll discuss those questions later this week.