Last week, Trump issued a series of executive orders to try and revive America’s nuclear power capacity, including reforming the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (to speed up regulatory approval) and advocating for more widespread deployment of advanced nuclear energy technology to support national security.

These executive orders came the same week the House passed its version of the budget reconciliation bill (the One Big Beautiful Bill Act), which includes cuts to various clean energy tax credits. Critically though, the bill in its current form1 includes a notable nuclear carve-out. While most clean energy projects must begin construction within 60 days of the bill being signed into law (and start providing services by the end of 2028) to still be tax credit eligible, advanced nuclear facilities only have to start construction by the end of 2028 to earn tax credits, giving nuclear far more lee-way than other types of clean energy.

This is not the first recent example of the US committing to expand its nuclear power sector. At the COP28 climate conference in Dubai in 2023, the US (along with over twenty other countries) pledged to triple global nuclear energy capacity by 2050.

In other words, both Biden and Trump have made commitments to nuclear.

However, whether or not the United States will truly develop its commercial nuclear capabilities depends on a few factors (things like cost, land use, and public tolerance for local nuclear power plants spring to mind). But one of the clearest bottlenecks of all is ensuring a stable, sufficient supply of uranium, the engine that runs the nuclear ship.

Uranium’s common nickname is Yellow cake, for obvious reasons.

America’s uranium supply

Before coming back online in 2024, US uranium production went into virtual hibernation for a few years.

Throughout the Cold War, the US was largely self-sufficient when it came to uranium. But for nearly forty years now, America’s uranium supply chain has completely turned over — it now imports virtually all of its uranium used in commercial nuclear reactors.

Despite ever expanding demands, not since the mid-80s has the US produced a material balance of uranium.

The question is, where does the US get its uranium from? Imports have historically been largely concentrated in a handful of big market players, most notably Canada. But Kazakhstan isn’t far behind (and, in fact, surpassed Canada in 2021).

Looking at those five countries listed above, one is Russia and two (Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan) are clearly in the Russian orbit. The other two (Australia and Canada) are theoretically US allies, but we all know how those relationships are trending.

Last May (2024), Biden signed The Prohibiting Uranium Imports Act, banning uranium from Russia, or Russian entities, through 2040. Russia responded with its own uranium export ban, restricting access to the US. Canada has ambitions to become the world’s leading uranium producer with a major billion dollar project awaiting final approval from the government (expected early next year). Assuming the government gives the go-ahead, operations would likely begin by early 2029.

The global uranium market

Possessing ~25% of global uranium reserves (both recoverable and merely identified), Australia has the largest supply of uranium in the world. Kazakhstan (~13%) and Canada (~10%) also have substantial reserves.

But while Australia has the largest uranium reserves, that doesn’t mean it is the top producer. As it stands, Kazakhstan is the undisputed uranium king.

Kazakhstan produces over 40% of global uranium, far surpassing its rivals in Canada, Namibia and Australia.

The chart above does a great job distilling down everything you really need to know about the current uranium market. While Kazakhstan mines the most uranium (43% in 2022), it does not possess any domestic nuclear energy facilities and thusly exports all of its product. Namibia and Australia are similar, producing 11% and 9%, respectively, of the global supply but utilizing none at home.

Meanwhile, the US consumes 26% of global uranium, but accounts for a mere 0.2% of its production. Russia and China both produce uranium, but nowhere near enough to cover their domestic requirements, while Canada produces a surplus that it is able to export abroad (largely to the United States).

If it doesn’t use the uranium itself, where does Kazakhstan send its uranium? You can probably guess. In 2023, over 80% of Kazakhstan’s uranium exports went to Russia or China, while the US accounted for less than 2%, and both have taken greater control in the Central Asian nation. Russia has deals in place with both Kazakstan and Uzbekistan to build nuclear reactors, ostensibly consolidating its geopolitical influence in the region. Last December (2024), a series of joint Kazakh-Russian uranium mining ventures in Kazakhstan also sold stakes to Chinese uranium mining firms. These transactions give China direct control over large-scale uranium resources, and the ability to leverage this control to help control market supply, and dictate prices.

China now sources virtually all of its imported uranium from Kazakhstan and Namibia.

Recent price developments

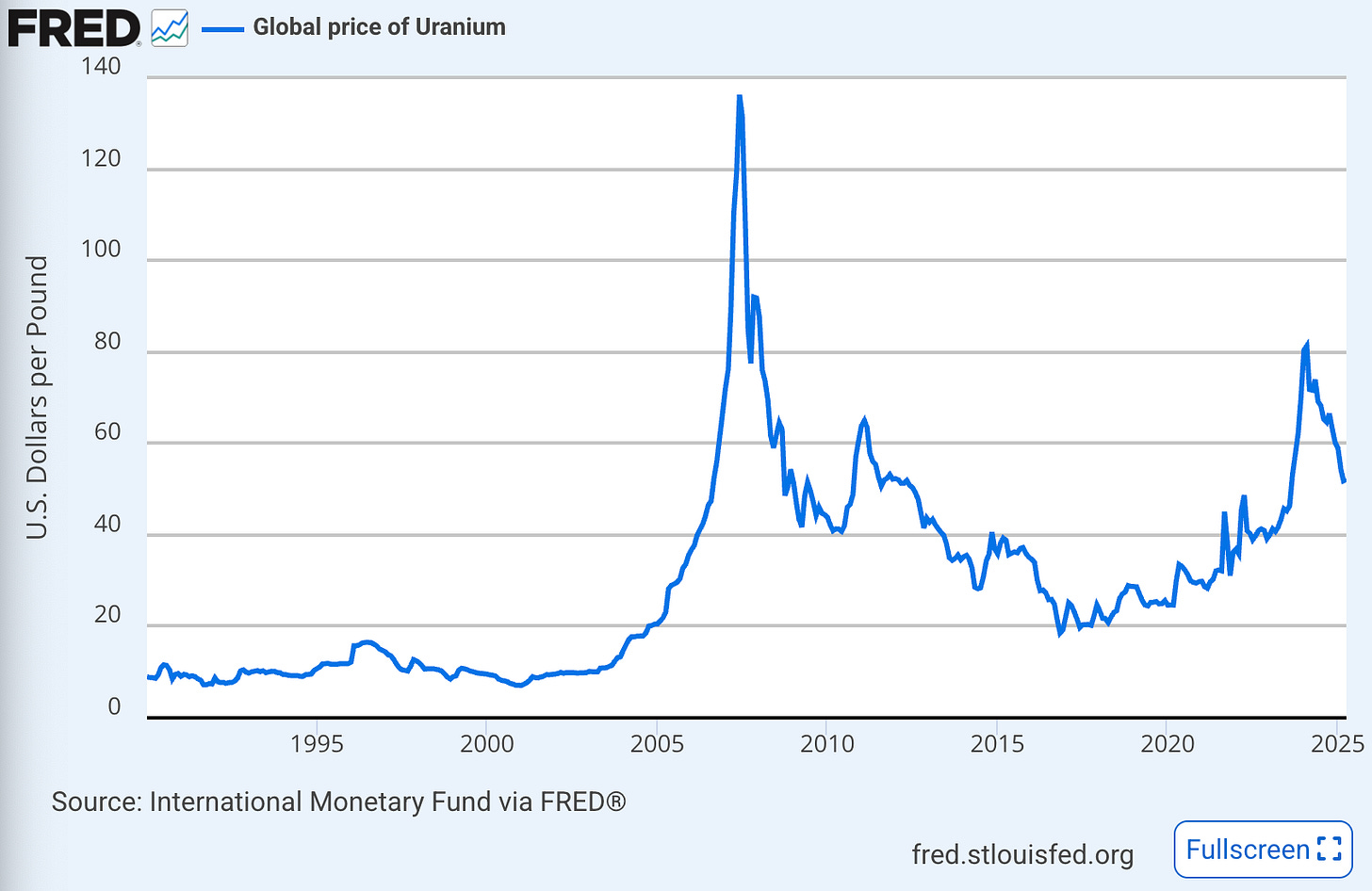

For years there has been a widespread underinvestment globally in uranium, largely because the price was so low (with a notable exception of that brief period pre-Global Financial Crisis) on the back of generally low demand for nuclear. That has recently shifted, and while the currently identified uranium reserves should be sufficient to meet nuclear capacity projections through 2050, this will require additional mining largely driven by market-conditions.

does it make economical sense to invest in large-scale mining projects?

does the political exist to ensure stable policies regardless of administration? what about the geopolitical tensions?

will tech companies (e.g., Microsoft and Amazon) take a more primary role themselves and invest directly in nuclear power, possibly in small-modular reactors, to support their ambitious data center plans?).

One area that had been spurring investment was the surging price of uranium, which took-off over the past half decade and had companies seeing $$. This price spiked throughout the early 2020s after a confluence of events including, the pandemic-induced shutdown of operations and the Russia/Ukraine war (both limiting global supply) coupled with increased demand after nations committed to increase nuclear capacity at COP28 in 2023 and the continued proliferation of data center projects requiring a constant supply of energy.

After over a decade of relatively controlled prices, supply constraints and additional clean energy commitments saw the price of uranium climb in the early 2020s. More recently, the price has cooled considerably as a large supply of Kazakh uranium entered the market and trade uncertainty leaves investors wary.

From a domestic perspective, the US has only a few mines operating, of which the lion’s share of production takes place at White Mesa Mill in Utah. But the recent price hike in response to increased commitments by the US amid simmering geopolitical tensions (which has some analysts predicting uranium prices could soar) mean additional production facilities are expected to reopen as uranium demand surges on the back of shifting government priorities and higher costs. In a sign of the times, last week the Trump administration approved the reopening of a uranium mine in Utah after an expedited review that lasted only 11 days. Approval processes have historically taken years because of the reviews required to assess environmental impact

What about recycling uranium, an idea explicitly called out in one of Trump’s EOs?

The idea of recycling nuclear fuel is actually more controversial than you might think, largely because doing so means extracting plutonium from spent fuel. This leaves some people worried about a greater supply of plutonium, and the potential for the further proliferation of nuclear weapons. While this might not be a massive risk in the US, which already has a large supply of nuclear weapons with heavy levels of security, openly advocating for recycling could lead other nations that utilize nuclear energy to pursue recycling themselves, and potentially create their own weapons.

There are currently no commercial fuel recycling facilities in the United States but to try and develop workable solutions, in December the Biden administration announced $10mn in funding for research into nuclear fuel recycling tech.

*******************

One recent assessment2 concluded that, at least through 2050, there is enough uranium readily accessible to satisfy global nuclear capacity growth (in both low- and high-growth scenarios) But in a similar fashion to other business interests in the year 2025, the report offers a word of caution. (PTO emphasis added)

Historically, strong market signals have driven significant investment in uranium exploration…However, various factors affect the timing and feasibility of resource recovery, including political stability, jurisdictional mining policies, and local experience with uranium mining.

To bring in-ground resources into production, market conditions must offer confidence in project returns. Poor market conditions delay not only new supply but also exploration investments, which impacts long-term resource development. For sustained uranium supply, both consumers and producers must ensure a stable framework for uranium exploration, mining, and transportation, supported by pricing mechanisms that encourage long-term investments

Political stability providing investment certainty begetting long-term commitments. The story of the moment, regardless of the sector.

If you enjoyed this edition of Nuance Matters, consider letting me know by buying me a cup of coffee!

Cheers!

Because its important to remember, the Senate still has to go through it.

Last month, the 30th edition of the Uranium Resources, Production and Demand report, a project jointly prepared by the Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), was released. Colloquially known as the “Red Book”, this report dives deep into all things uranium, including the past and future markets.