How to Feed the World

A recent book offers some sage advice: ignore the doom-sayers and make a few small changes to help alleviate the stress in the food system.

With a title like How to Feed the World, a prospective reader might expect author Vaclav Smil to provide a treatise on everything wrong with the world. But this book is not a call for radical action. As he notes in the opening pages, Smil’s book is “the opposite: it argues for the power of incremental changes.”1

How to Feed the World is short (just over 200 pages, with 50 pages of notes / credits) and dedicated to the facts.2 It doesn’t provide dramatic lessons or world-changing innovations, but instead grounds the reader in an understanding of how the world works. In doing this, Smil hopes that “it is far less likely you will make incorrect interpretations or misunderstand the basic realities of food, nor will you accept uncritically the many exaggerated claims and unrealistic promises regarding the future of global farming.”

The book is stuffed (perhaps overstuffed?) with facts. Sentences like, “Botanists have classified nearly 400,000 species of vascular plants, some 12,000 of them grasses producing small, nutritious seeds; but only a tiny share of all plants have been domesticated. Just 20 species account for 75 percent of annually harvested crops, and today, just two domesticated grasses—rice and wheat—provide 35 percent of global food energy.”3 are common.

I’ll be honest, when it came to the onslaught of facts and figures, my layman’s eyes sort of glazed over. Smil clearly has an eye for cold, hard data, but when incorporated into a 200-page book, it can be a bit overwhelming.

*********************

One of the overarching narratives in this book is supply variance. Over the past 50+ years, we have made remarkable strides in feeding the world. While the world produces enough food daily to feed the global population, the locational dispersion and sheer mass of food waste mean that hundreds of millions of people do not have access to enough food on a daily basis.4 Back in 1970, 30% of the global population was under- or malnourished. This figure is down to 10% today, heavily concentrated in Asia and Africa.5

Global food production averages ~3,000 kcal/person, but varies by location. At the same time, daily food waste is ~1,000 kcal/person.

With this backdrop, Smil offers two key take-aways, both of which involve doing less rather than doing more. They are:

Reduce food waste, and

In wealthier countries, moderate high rates and change the composition of meat consumption over time.

Food waste

Our ability to store food has evolved over the centuries. Back in medieval times, staple grains were stored in structures made of mud, wood and grass that could lead to losses of almost half the entire stored crop. But innovations in silos and steel bins have reduced storage losses to closer to 1-2% today. While this is a remarkable achievement, the aggregated losses across the whole supply chain (from harvest to point-of-sale) remain unconscionably high, especially in lower income regions.

Around 15% of staple grain crops, like rice from China and Thailand or wheat in sub-Saharan Africa, is wasted, despite their being massive food inequality in some of these locations.6 Overall, as a percentage of total municipal waste, food waste increased from 13% in 2005 to 22% in 2018.7 You’ll probably be unsurprised to learn that the country responsible for the most waste is the United States.

In 2022, the US wasted more food per capita than any other mass population, predominantly at the household level.

In the US, crop production accounts for 80% of irrigated water usage, but the sheer volume of food waste means that 25% of all irrigated water goes toward uneaten food (on top of adding 35mn tons of waste a year to landfills and accounting for 4% of US crude oil consumption).8

Beef’s role in the food system

Smil tracks three reasons for way beef has become such an important staple in global diets,9

The displacement of cattle as a the most important source of traction in farming,

The rise of beef as an international export commodity during the second half of the 19th century, and

The rise of the internal-combustion engine made horses less essential, which allowed farmers to convert land previously devoted to horse feed toward cattle.

But of course, because of cattle’s land, feed and water requirements (not to mention their methane-related carbon emissions), cattle are not the best source for meat. Today though, after over a century’s worth of inertia, eliminating it from modern diets is neigh impossible. It isn’t just beef though, all meats are an essential aspect of the American diet. In 2021, the US spent $160bn on meat, including $120bn on fresh-cut meat (the other $40bn on processed meat). That compares to just $1.3bn on meat-substitutes and a lowly $350mn on tofu.10

The emission impact of various meat-based proteins (+ farmed fish).

How to respond

It is important to note that Smil is not a died-in-the-wool vegan or wholly anti-carnivore. He eats meat and recognizes the importance of a balanced, varied diet that includes the protein and nutrients derived from animal products. His proposed solutions to these problems are not radical changes, but rather small-scale shifts in practice and philosophy that can go a long way.

Regarding waste, he suggests more crop rotation and more water-efficient crops to reduce the land stress and make the harvests more resilient to the fluctuating climate. In the US, restaurants and stores need to embrace smaller serving sizes and different packaging, since so much food is tossed because people are “full” or because the “Best by date” is past. Additionally, where food waste is necessary (e.g., an apple core, a banana peel, or the skin of an avocado), composting to help revitalize soil could go a long way.

Regarding the change in meat composition, the simplest solution is to consume more chicken, which has a fraction of the feed and land requirements as beef, even in a free-range situation as opposed to the industrial farming set-up that has proliferated across the modern world.

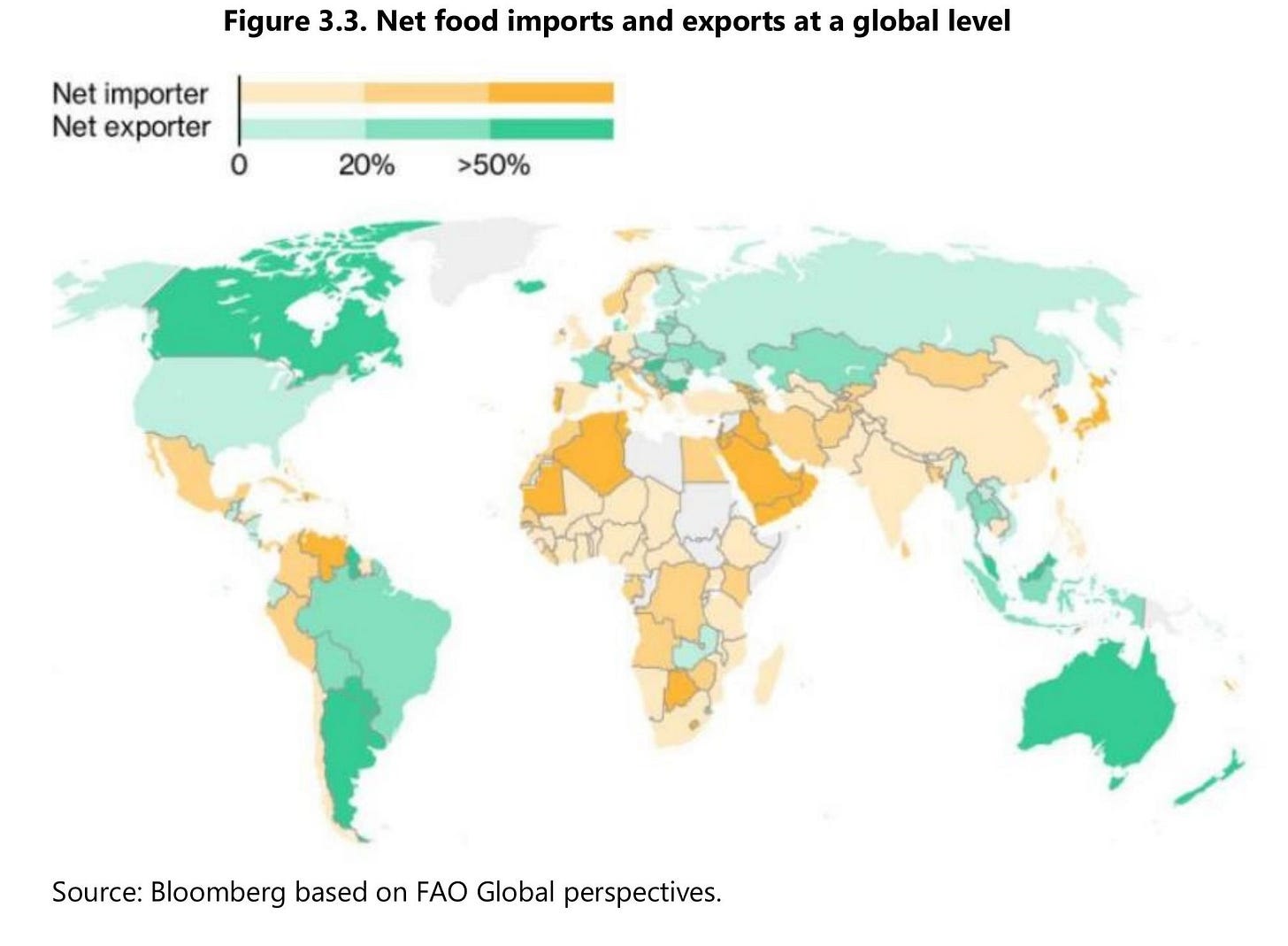

Of course, part of this solution assumes we live in a globalized system where food products can be easily shipped across the world. Today, industrialized countries like Japan and South Korea import 60% of their food supply, so this is clearly an integral aspect of global supply chains.11

But what happens if we erect trade barriers, de-globalize and shut national economies off from each other? This would force communities to rely on what they can harvest locally, even where the climate doesn’t support it, merely entrenching inequality within the global food system.

Whether you are an importer or exporter, the global food trade matters to everyone around the world.

We can live with more expensive iPhones and cars. But food? Not so much.

*******************

Post-script

To end on a lighter note, Smil points out the stark visual difference between wild bananas, which are full of small hard seeds that make them very difficult to eat, and domesticated ones, where the seeds are “dark specks” concentrated in the center of the banana.

Wild bananas vs bananas consumed by humans

Wild indeed!

If you enjoyed this edition of Nuance Matters, consider letting me know by buying me a cup of coffee!

Cheers!

Smil, Vaclav. How to Feed the World. Viking. 2025. pg 2.

Smil is the author of over thirty books, ranging from such titles as “The Bad Earth” to “Number’s Don’t Lie”, it is clear Smil is not someone to rest on his laurels.

ibid. pg 29.

Ignoring external events like war and war-induced famines that are also damaging.

ibid. pg 127

ibid. pg 43.

ibid. pg 112.

ibid. pg 177.

ibid. pg 84.

ibid. pg 133.

ibid. pg 146.