Is India about to attack Pakistan?

I sure hope not. The last thing the world needs right now is for two nuclear-armed neighbors to unleash hell upon each other.

When one nuclear power claims another nuclear power is complicit in a terrorist attack, and is possibly readying a military response, you would think that would be the most important story in the world. Alas, among the litany of other geopolitical developments, it has been relegated largely to the sidelines.

Today, we walk through what is happening in Kashmir between India and Pakistan.

The inciting incident

Last Tuesday (April 22) in the vacation town of Pahalgam in the Indian-controlled portion of Kashmir, armed men opened fired on a group of Indian tourists, killing 26 men, 25 Indians and one Nepalese citizen.

Kashmir is a Muslim-majority territory in the Himalayan mountains claimed by both India and Pakistan. Based on an agreement that stretches nearly 80 years, India controls 2/3rds of Kashmir while Pakistan the other third. By population, this breaks down to around 10mn people living in the Indian-controlled section and 4.5mn in the Pakistani-administered portion. Another portion is controlled by the Chinese, but it is largely high altitude desert terrain and sparsely-populated.

How India, Pakistan and China each view Kashmir

The attack was the deadliest on Indians in Kashmir since 2019, when a suicide bomb killed 40 Indian military personnel. Back then, India and Pakistan engaged in an escalating (though largely contained) tit-for-tat before international diplomatic pressure ultimately tempered the situation. State-loyal domestic media praised the efforts of their corresponding governments, and crisis was averted. Later in the year though, the Indian government revoked Kashmir’s constitutional autonomy, controversially bringing the region under direct Indian control.

Who is responsible for the attack?

The Resistance Front, a militant group the Indian government designated a terrorist organization in 2023, posted a message on the Telegram app claiming responsibility for the attack. But a few days later, in a move that has further convoluted the situation, the group rescinded its statement of responsibility, saying its social media account was hacked.

While the Resistance Front formed in 2019 and is a relatively new commodity, Indian intelligence claims the terrorists were supported by Pakistan and are merely a cover for Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT). LeT is a Sunni militia founded in the late 80s/early 90s with a goal of annexing Kashmir and rose to international prominence after the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai when gunmen killed 166 and injured another 300 people. The LeT is a designated terrorist organization by India and the US, among others.

India has long asserted Islamabad backs militant groups targeting Indian interests, and claims LeT is supported by the Pakistani military and its main intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence Agency (ISI). While there is little dispute regarding the Pakistani government’s support for LeT in the 90s as a proxy against India, the movement was banned in 2002 and the government now denies links to LeT.

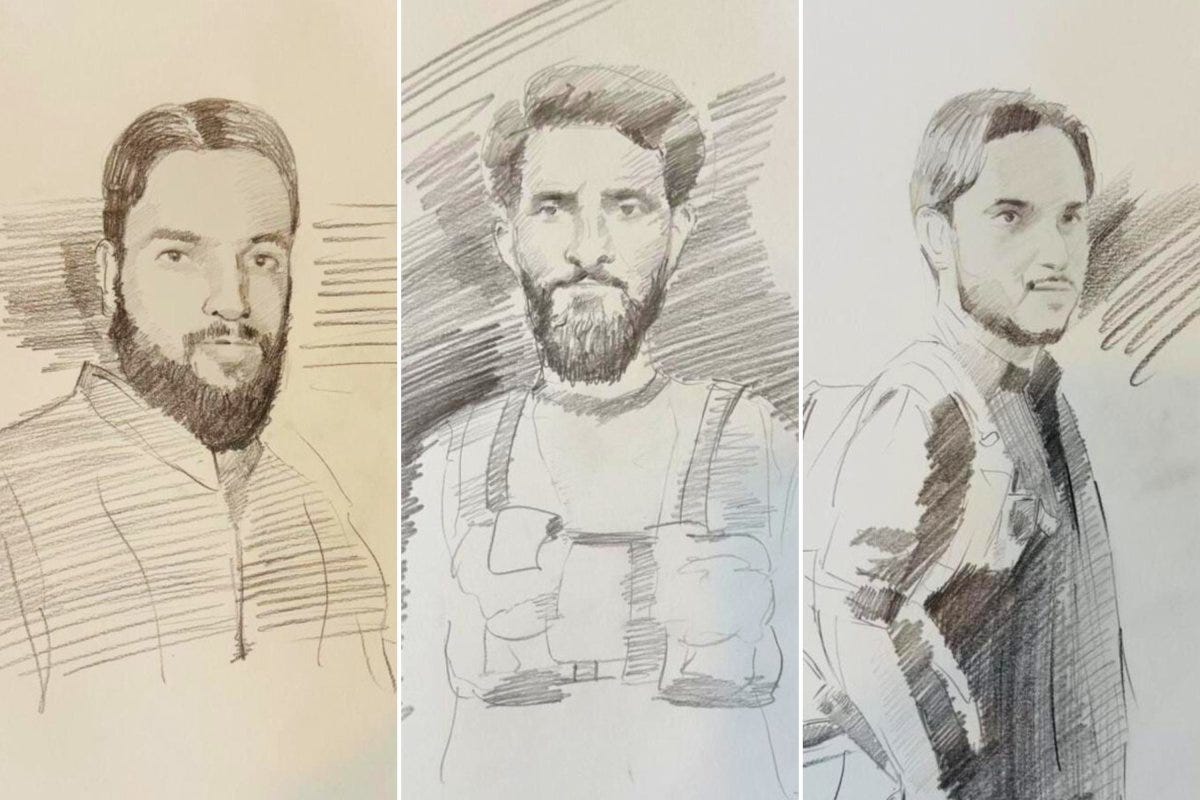

The Indian police have named three of the four suspects, asserting two are Pakistani nationals / members of LeT and another is a local Kashmiri (the fourth man remains unknown).

The sketches of three of the four suspected assailants per the Indian authorities.

Indian forces are scouring the region in search of the suspected terrorists. Thus far they have detained thousands of people for questioning, destroying Kashmiri property in the process.

Shortly after the attack, Islamabad released a statement expressing condolences and rejected any Pakistani complicity in the attack, saying that Indian finger pointing was an attempt by India’s prime minister Narendra Modi to divert attention away from his own administration’s security failures. In a closed-door meeting in New Delhi last week, the government acknowledged there were security lapses that precipitated this strike.

Pakistan’s defense minister has reiterated that his country had nothing to do with the attack and was ready to cooperate with any international investigation. Further to the point, over the weekend Pakistan’s prime minister Shehbaz Sharif called for an independent investigation into what happened.

Escalating tensions

New Delhi immediately banned Pakistani nationals from entering India, including expelling Pakistan’s military advisers, suspended Pakistani visas, and downgraded diplomatic ties.

Though Pakistan termed the Indian moves “politically motivated and legally void,” Islamabad responded in-kind, including shutting down the Indian trade transit through Pakistan, closing Pakistani airspace to Indian owned and operated planes, and suspending its participation in bilateral agreements with India. One such arrangement is the Simla Agreement, which for the past 50 years has demarcated the India-Pakistan border (by creating the Line of Control) and been used to peacefully resolve tensions.

India and Pakistan though have not had great relations for a while and, with trade largely suspended since 2019, their economies do not rely on each other. So most of these moves were more symbolic than anything else. That being said, one move is drawing more attention for its potential long-term impact.

The Indus Waters Treaty

India suspended is participation in the Indus Waters Treaty of 1960 (IWT). Brokered by the World Bank a decade after India temporarily shut off Pakistan’s water access, the IWT provides for the equitable use of water flowing from the Indus River and its tributaries and has been one of the most important transboundary agreements anywhere in the world. India is the upstream power in this relationship, so it arguably has the leverage. While India is able to utilize the water that flows to Pakistan for non-consumption purposes (e.g., hydropower), the IWT dictates India is not allowed to disrupt the flow in anyway that would harm Pakistani access.

Despite previous cross-border tensions causing India to threaten the viability of the agreement, the IWT has stood the test of time. But a potential rupture after this most recent attack threatens that union and underscores the changing geopolitical climate. Around 80% of Pakistan’s water comes from the Indus River Basin, contributing toward 25% of the nation’s GDP, and the government has labeled India’s weaponization of the treaty to be a form of “water warfare.”

The Indus River Basin supports over 300mn people, predominantly in Pakistan and India.

Pakistan’s geography dictates that it needs this water a lot more than India, and the country is already enduring significant water shortages as a result of climate change. While it is not possible for India to immediately stop the flow of water into Pakistan, it could assert more control over the Basin by developing additional infrastructure like dams. In the long-term, these developments could change the predictability of water flows, impacting Pakistan’s irrigation system and hindering the ability of Pakistani farmers to plan for their crop growing seasons.

Will India attack Pakistan with force?

Claims by Indian officials and witnesses that Hindu tourists were specifically targeted by the attackers has heightened tensions and might have pushed New Delhi into a corner where it needs to forcefully respond and there is some concern India is developing a case for a strong military response. Modi has spent the past decade cultivating a strongman image, especially in Kashmir, which he has worked to reimagine as an Indian tourist destination, though largely through repressing Kashmiri rights.

In a speech following the attack, Modi said India would do whatever it takes to bring those responsible to justice.

India will identify and punish every terrorist and their backers. We will pursue them to the ends of the earth. India’s spirit will never be broken by terrorism. Terrorism will not go unpunished.

The speech was made in English not Hindi, an unusual move for Modi suggesting the message was meant for consumption beyond just India and Pakistan, but the broader international community.

The day after the attack, the spokeswoman for India’s opposition Congress party took to X to say Rawalpinidi (home to Pakistan’s military) “should be flattened” and that it was “time to teach Pakistan a lesson they don’t forget.” Since the attack, Kashmiri students studying in India and other Muslim persons have been targeted by Hindu groups, amid fears of growing oppression against the minority group.

On Tuesday (April 29), reports out of New Delhi indicated Modi has given the Indian armed forces the go-ahead and “complete operational freedom” to do whatever it deems necessary to respond to the attack. Pakistani intelligence then said it had credible evidence India was planning imminent military action against Pakistan while reiterating that India had not provided a “shred of evidence” regarding Pakistan’s involvement in the attack.

Early Wednesday morning, there were reports of Indian fighter jets flying over Kashmir, appearing to patrol the Line of Control without crossing over. Reports of gunfire across the Line of Control have continued since they began at the end of last week.

The domestic situation in Pakistan is also a bit tenuous. The most popular politician, Imran Khan, remains in prison while the powerful military is severely unpopular. Engaging in a conflict with rival India over Kashmir could do wonders for the military. Pakistan’s stated mentality of ‘quid pro quo plus’, dictating that it will not take any strike lightly and in fact look to impose a greater cost on India, also risks the situation spiraling out of control. Pakistan’s foreign minister said that his country would not attack India, but reserved the right to retaliate should New Delhi follow through on its threats.

Wither global mediation?

As tempers flare, international actors, ranging from Iran and Saudi Arabia to the EU to the UN, have cautioned restraint, and offered to mediate a sit-down. But in this moment of particular global chaos, with world leaders concentrating elsewhere (principally Ukraine/Russia, and the tariff wars)1, it is not unreasonable to think they have little bandwidth to respond to an India-Pakistan break.

And while the US has advocated both sides work toward a “responsible solution” to the situation, the Pakistanis are worried geopolitical and economic considerations (principally, India’s role against China) would result in the US migrating toward India’s corner if tensions break and further violence ensues. The last time we came close to a clash between India and Pakistan, in 2019, the US and allies helped defuse the situation by pushing negotiation and restraint. Despite the US president being the same person six years later, the geopolitical landscape looks starkly different. With US troops no longer in Afghanistan, US interests in the region are reduced (and the US does not have a formal ambassador in place in either India or Pakistan).

A change in the IWT though would not come without major geopolitical risks for India, especially with neighboring China and Afghanistan who also utilizes resources from the Indus Basin. China’s upstream control of rivers that support hundreds of millions of Indians, coupled with China’s partnership with Pakistan, means India’s unilateral decision to end the IWT could further raise temperatures in the region

***********************

New Delhi’s response clearly suggests it feels the Pakistani government is responsible for this attack. But too be clear, the Indian government has not produced any credible evidence proving Pakistan’s complicity in the attack.

Modi and India have a choice:

Send missiles at military targets in Pakistan proper, risking real escalation,

More limited air strikes along the border in Kashmir, to present an image of response while really de-escalating, or

Conduct a thorough investigation and present any evidence of Pakistan’s complicity to the international community before doing anything which can’t be undone.

For the sake of everyone, door #3 needs to be the response. Because there is one thing we do know: both India and Pakistan are nuclear powers, and they don’t particularly like each other.

If you enjoyed this edition of Nuance Matters, consider letting me know by buying me a cup of coffee!

Cheers!

Much less so Gaza, Sudan and elsewhere.