It is impossible to justify doing business in Xinjiang.

This isn't new, but was reinforced last month after the results of a social accountability audit on Volkswagen's operations in the region were leaked.

The Uyghurs in Xinjiang

The Chinese region of Xinjiang, located along the country’s northwestern border, is the epicenter of much of China’s resource wealth. It is also one of the country’s most important manufacturing outposts, with domestic and international companies possessing factories in the region. And as China has expanded its renewable energy capacity, Xinjiang stands as one of the main locations for the country’s vast solar photovoltaic (PV) power stations.

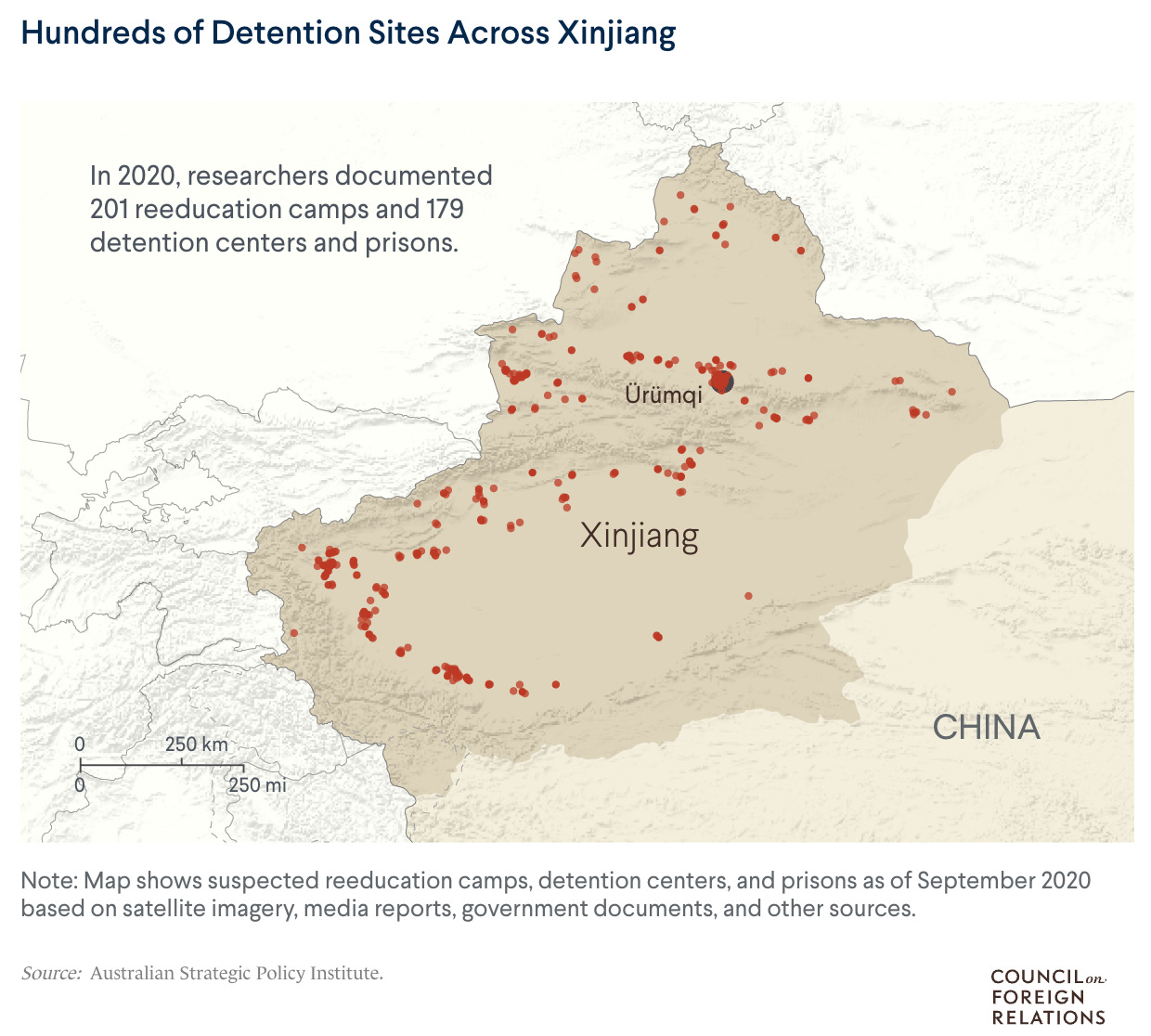

Xinjiang is also home to over 10mn Uyghurs, a mostly Muslim, Turkic-speaking ethnic group. Over the past decade, human rights advocates have accused China of subjecting the Uyghurs to widespread abuse and forced labor. Reportedly one million Uyghurs have been placed in ‘reeducation camps’ where detainees have been subjected to brainwashing and torture. A campaign of intimidation and fear against the Uyghurs by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has spread abroad, as the government has sought to control the family members of those Uyghurs who have left Xinjiang.

As the issue gained salience in the US and Europe, governments started to take action. In 2021, the US and allies sanctioned Chinese companies and individuals operating in the region and thought to be responsible for the Uyghur abuse. In June 2022, the US enacted the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, which bans goods produced in Xinjiang unless it can be proved they were not produced via forced labor. A few months later, the UN published a report acknowledging there was credible evidence China had committed crimes against humanity against the Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

Volkswagen’s operations in Xinjiang

Earlier this year, the German industrial giant BASF sold its last two Xinjiang-based plants. This made Volkswagen (VW) the last major German company to have a factory in the region. The plant, which VW runs as a joint-venture with Shanghai-based SAIC Motor Corporation (a Chinese state-owned enterprise) hasn't produced cars for a couple of years and today operates as mainly a distribution hub. But the company's agreement with SAIC runs through 2029 and, conscious of the impact this might have on VW's image in China, VW is hesitant to pull-out before the agreement is up.

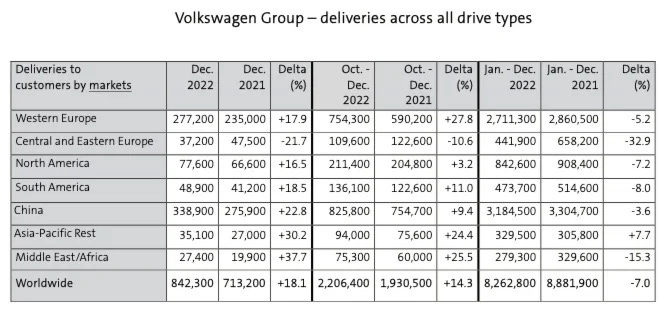

Operating in the region since 2013, the German car giant was well-aware of the criticisms and allegations of human rights abuses, but has stayed relatively quiet on the matter. And it doesn’t take much of an automotive expert to figure out why. Below is VW’s 2021 and 2022 sales by country. Responsible for ~40% of sales, China was far-and-away VW’s largest market.

Speaking out against the CCP or acting in Xinjiang would have put a target on VW’s back. Companies like H&M and Nike had recently taken heat from the CCP and Chinese media for speaking out, resulting in implicit product bans (China accounted for ~15% of Nike’s revenue in recent years). VW didn’t want to jeopardize its spot in the critical Chinese market, which the company’s chief executive had extolled earlier this year as VW’s “second home market”.

But last year, MSCI, the rating firm, gave VW a ‘red-flag’ for its Xinjiang operations, warning investors that it was impossible to justify investing in VW for sustainability reasons. This quickly got management’s attention.

With the company’s generally sluggish response to the global transition to electric vehicles, the company’s share price had been struggling since the end of 2021. MSCI’s red-flag marked the company a pariah amongst the investment community, making the company’s attempts to raise additional capital that much more challenging (and expensive).

To address the problem, Volkswagen hired Löning, a German human rights and corporate responsibility consultancy founded by Markus Löning, a former member of the German Bundestag and Human Rights Commissioner, to audit its Xinjiang facility and demonstrate that the operations functioned without forced labor.

Dec 2023 - The results of the audit

Executing the audit with a China-based law firm, Löning claimed the process included ~40 interviews at a factory with 197 workers and and free access to inspect the factory.

Once the audit was completed in December 2023, Löning reported that it “could not find any indications of evidence of forced labor among the employees.” But Markus Löning also stated “the challenges in collecting meaningful data for audits [in China and Xinjiang] are well known” and that this audit was no exception.

As a result of the report’s findings, MSCI removed the ‘red-flag’ from VW.

Shortly after the results were made public though, Löning faced an internal staff revolt. The company’s 20 employees, excluding the founder and another executive, wanted it known that they did not agree with the audit’s findings. Löning employees indicated that “no other team member from Löning participated in, supported or backed this project.” Löning himself then said in an interview that the crux of the audit had been a review of documentation, not interviews, which he himself said could be “dangerous”.1

Sept 2024 - The leaked report

Nine months later, this story is back after the audit report leaked last week and experts concluded the audit itself did not adhere to international standards. The report, released to a handful of news agencies by the Campaign for Uyghurs, found that the Chinese law firm that worked with Löning did not abide by the internationally recognized SA8000 social auditing standard. It also noted the Chinese law firm that had participated in the audit was Liangma Law, a firm with extensive ties to the CCP.

In summarizing this result, Judy Gearhart, a professor who helped develop the SA8000 regulations, stated “the conclusion of [VW’s] press release is not substantiated by the audit.”

An analysis of the full audit report by The Jamestown Foundation, a non-partisan think tank focused on Eurasian security and policy, found (PTO emphasis added)

Volkswagen’s statements about the audit are misleading or false.

Liangma’s claim that the audit “assessed compliance with the Social Accountability 8000 (SA8000) standard” is contradicted by the report itself.

Publicly available information suggests that the persons in Liangma’s auditing team had no substantial prior expertise in conducting a social audit or an SA8000.

The audit’s methodology and scope are unsuited to meaningfully assess the presence or absence of forced labor at the factory.

Notably, neither Löning or Liangma have the proper accreditation to perform SA8000 audits, a fact made clear by the conduct of the audit. As Der Spiegel (one of the media organizations which received the leaked report) noted, (PTO emphasis added)

According to the audit report, eight members of management and 32 factory workers were interviewed. First, though, a "group briefing of interviewees” took place inside the factory. The lawyers noted that the room was spacious, roomy, well lighted and with central heating. They also wrote "that all interviewees were very relaxed and with smiling faces.”

The problem, though, was that because all of the participants were apparently at the briefing, everyone knew who else was taking part. Anonymity was no longer possible. Which, it goes without saying, is not the optimal situation when it comes to speaking openly about possible problems in a dictatorship.

Additionally, it appears that general staff were not asked about forced labor, and instead were asked closed-ended questions like "Have you ever experienced any issues relating to unpaid wages, overtime pay, or unsafe working conditions?" where the only possible answers were "yes" or "no" with little chance for an open discussion. As you might expect, all of the interviewees’ responses were concise and to-the-point, noting that life in the factory was alright.

Even if the interviews had been expansive conversations, this would have spelled disaster for the workers. One of the most damning details of the leaked report is that interviews with factory workers were live-streamed to the law firm’s Shenzhen-based HQ. Remember, the law firm is connected with the CCP, so by having a live broadcast of the interviews, the workers were placed in a situation where their confidentially could not be guaranteed.

What incentive would they have to speak freely, and potentially incriminate their bosses, if the result was their own persecution?

Based on the personnel involved, it appears no one really took this audit seriously. One of the auditors employed by the Chinese law firm, Clive Greenwood, had only joined the law firm shortly before the audit commenced.

I guess that is reasonable, maybe he was in the process of switching jobs and this was the first project available.

But about a year before participating in the audit, Greenwood had posted to LinkedIn his thoughts on social accountability audits in China.

In Greenwood’s view, an audit over social accountability in China was worth peanuts, or was aka useless.

The Jamestown Foundation did a deep dive into Greenwood’s history, and it is interesting (to say the least).

Until 2013, Greenwood ran a bar, The Drunken Chef, catering to foreigners in the Chinese city of Suzhou. According to LinkedIn and formal business filings, he returned to the UK, where he was as recently as 2019, before returning to China in Jan 2020 to establish a quality control firm to conduct audits for small to medium-sized European companies. His next few years are a bit of a mystery, but based on his publicly available information, there is no evidence to suggest that, prior to joining Liangma, Greenwood ever conducted an SA8000 audit or social audit with a focus on forced labor.

How he got a role in the factory audit, and as one of only three authors on the report, is anyone’s guess. Greenwood did not respond to Der Spiegel’s request for comment.

Following the leak of the report, a coalition of international politicians, including a number from Germany’s governing coalition, called on Volkswagen to withdraw operations from Xinjiang.

China’s retort

Last week, China’s Ministry of Commerce announced plans to investigate whether PVH, the company which owns Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger, had taken “discriminatory measures” against apparel produced in Xinjiang.

The ministry indicated PVH would be investigated by the Unreliable Entity List Working Mechanism Office. The Unreliable Entity List is basically China’s version of a blacklist, and currently only includes a handful of companies. The most notable on the list include the defense companies Lockheed Martin and Raytheon, who were added last year for selling arms to Taiwan. But as American defense firms, they aren’t exactly free to do business with China anyway, so this isn’t a major loss. A ban on a clothier like PVH would be much more of an escalatory move.

********************

Considering the shroud of secrecy that much of China operates under, it shouldn't come as much of a surprise that an audit would produce results as flimsy as a feather in the wind. This only reinforces that businesses and governments should not be operating in Xinjiang, or any location globally, when they cannot independently assert and verify the labor conditions are up to global standards.

Admittedly that can be difficult. Nearly 10% of the global supply of aluminum is sourced from Xinjiang, used by automakers around the globe (including GM, Toyota and Tesla). So these companies might have to purchase more expensive materials or utilize factories that require more expensive labor, hiking up prices as a result.

Yes, people are still pissed about price levels and inflation. But that is a small price to pay to ensure reasonable labor standards.

A few weeks later, Handelsblatt, a German newspaper, published allegations that in 2019, forced labor was used to built a test track in the region for VW cars, which was not within the scope of the audit.