In December, the Japanese firm Nippon Steel agreed to purchase US Steel for $14.9bn. Nippon Steel defeated rival steelmakers Cleveland-Cliffs and ArcelorMittal in an auction for the US public steel firm.

At the time, Nippon’s purchase price represented a 40% premium over US Steel’s share price. It isn’t just that Nippon Steel is willing to pay a lot for US Steel. It is willing to pay a lot more than any one else was willing to pay. In August Cleveland-Cliffs, an American rival, had a $7.3bn bid rejected by US Steel.

After the Nippon deal was announced, the price of US Steel promptly shot up 25%. From a pure economic stand-point, this seemed like a win for US Steel.

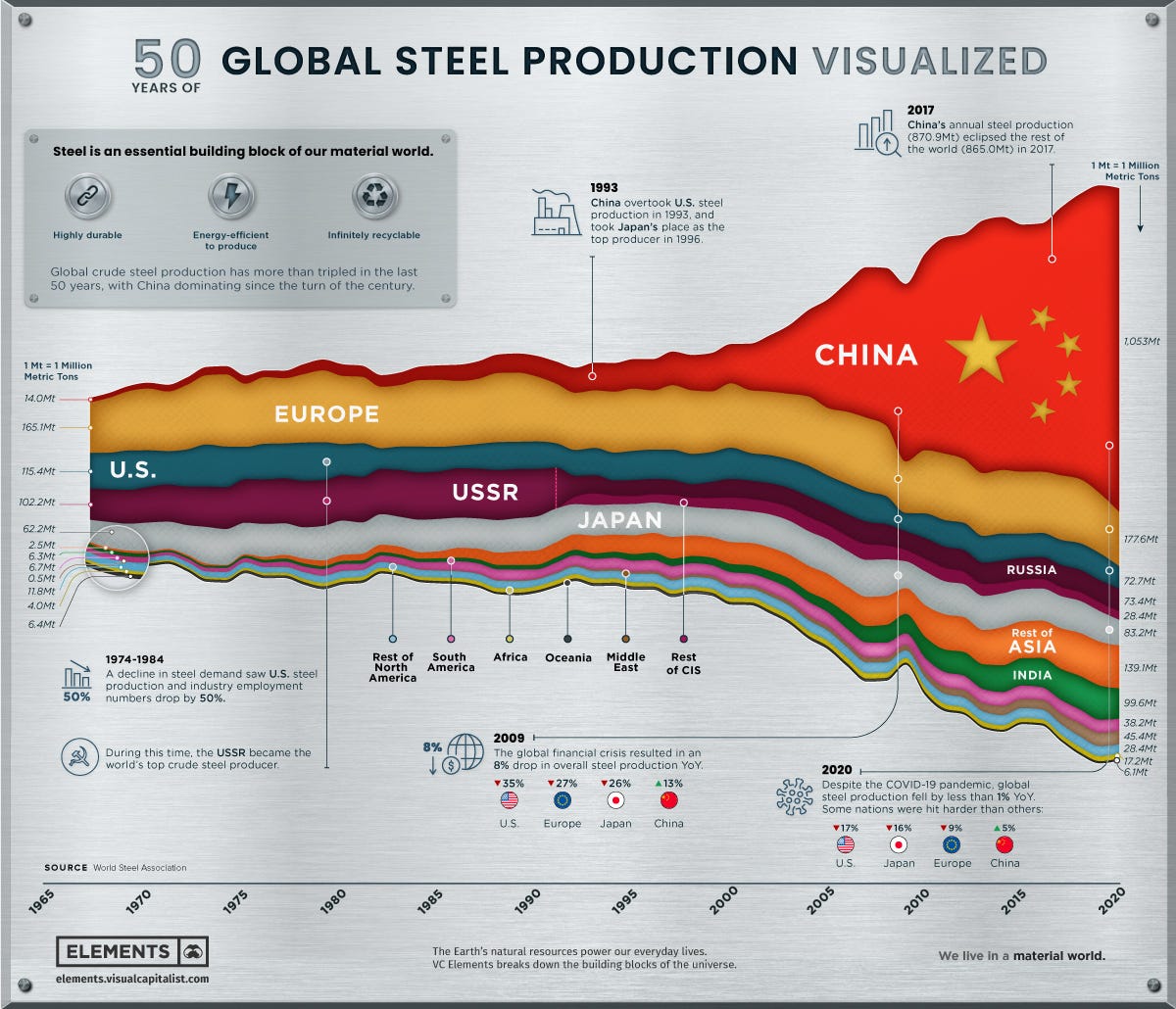

Nippon Steel is the fourth largest steelmaker in in the world, last year producing ~44.4mn metrics tons of steel. Meanwhile, US Steel produced around 14.5mn metric tons in 2022.

In fact, the US hasn’t been a major player in the steel industry for a long time. In an implicit acknowledgement of this fact, US Steel has laid off ~8,000 employees since 2017.

China dominates the steel industry. The US and Japan are relative minnows.

At a more macro level, the US and Japan are pretty close allies. The US relies on Japan to host a number of large US military installations, and to play an important geo-strategic role against China. And as China is much closer geographically-speaking to Japan, with an extensive history of military conflict, China represents a much larger threat to Japan than the US. The US and Japan also, along with Australia and India, make up the maritime alliance known as the Quad.

So you would think that Nippon Steel offering to purchase US Steel, a tired old warrior in the industry, for nearly $15bn - a price well above what other bidders were willing to pay - would be a relatively easy transaction to countenance.

But alas, that is not the case.

Biden opposes the deal

Last week, Biden publicly came out against the deal, arguing it went against American interests. He said it was “vital” US Steel was “domestically owned and operated”.

As one might expect when the US President openly declares his thoughts on a policy matter, the markets reacted. And in this instance, they reacted quite negatively.

After Biden denounced the deal, he also signaled he had been in touch with the president of the United Steelworkers union to confirm that he would stand with the steelworkers.

Across North America, the United Steelworkers union has 1.2mn members and retirees. After Cleveland-Cliff’s bid was rejected in August, the United Steelworkers’ union indicated that it supported that deal and it would “not endorse anyone other than Cliffs for a transaction.” And sticking with this script, the union immediately voiced its displeasure after the deal was announced in December. The union argued US Steel was prioritizing a foreign corporation over domestic labor. To try and stem the tide of negativity, Nippon Steel responded by promising to honor the current agreements between the union and US Steel.

Yes, the Japanese labor market has historically been notorious for its inadequate wage structure. But we might be seeing the beginnings of a new Japan. Earlier this month, large Japanese corporations - including Nippon Steel - agreed to give workers the largest pay increases in decades. Nippon Steel even went above and beyond what union workers were asking, granting the company’s largest monthly pay hike since 1979! at almost 12%. Could this have been a play to appease the United Steelworkers union? Perhaps.

And as noted above, the US steel industry in general has not been on a hiring spree of late. While employment has recently been pretty flat at around 80,000 workers (total in the US), this represents a more than 50% drop since 1990. As the economist and commentator Noah Smith surmises, the panic around Nippon Steel’s potential acquisition is really just a general lament for America’s shrinking irrelevance in manufacturing and industry at-large.

The stories about U.S. steel all mention that it’s “iconic” — it was started by Andrew Carnegie! — and its merger with a foreign company just seems to underscore how far the once-mighty American steelmaking industry has fallen. Total steel production is lower than it was half a century ago:

In terms of tonnage, it’s lower than in the 1950s. And as a fraction of overall industrial production, steel is a faint shadow of what it once was:

In corporate terms, U.S. Steel itself is a paltry thing — even at the huge premium that Nippon Steel paid for it, its purchase price of $14.9 billion was still only about three quarters of what Adobe wanted to pay for the online design tool Figma.

Blocking the acquisition of U.S. Steel will do precisely nothing to reverse or even slow the U.S. steel industry’s seemingly terminal decline.

So if the steel industry isn’t all that material to the US economy, and it doesn’t real stand a chance of rebounding any time soon, why did Biden announce he was against the deal? I’ll give you one guess.

Politics, politics, politics.

Prior to Biden’s statement last week, the deal had already drawn bi-partisan animosity from the Hill. Senators from across the aisle, including Pennsylvania Democrats John Fetterman and Bob Casey (where the main US Steel plant is located) and Republicans JD Vance (Ohio), Josh Hawley (Missouri) and Marco Rubio (Florida), all opposed the deal.

Biden has described himself as the most pro-union US President ever. However, union members views on Biden have been sliding. After winning 56% of the union vote in 2020, recent polling has Biden in a virtual tie with Trump for their vote. True, this follows a similar polling pattern seen throughout the electorate where Biden’s age and inflation are weighing on voters minds. But if Biden is going to win in November, he has to make incremental improvements somewhere.

Trump has already come out against the deal, saying that if he were president he would “block it instantaneously”. This put Biden in a political bind. Support the deal, and he risks the wrath of union members, especially in the swing-states of Pennsylvania and Michigan where US Steel has manufacturing plants. A Pennsylvania and a Michigan that Biden won by 80,000 and 150,000 votes, respectively in 2020 and needs to win in November. And while only ~10% of American workers are unionized, two-thirds of Americans approve of labor unions. Overall, unions are enjoying their highest level of sustained support in the US since the 60s.

So if Biden supported the deal, and went against the unions, Republicans could play this on a loop for the next 8 months and Biden’s pubic perception as pro-union (and by extension, pro-American worker) could tumble.

But by opposing the deal, just like Trump, Biden has exposed himself to accusations of hypocrisy and not valuing our allies. People like Michael Strain of the moderately conservative American Enterprise Institute1, have called Biden’s decision “a sign that protectionism has run amok”. Peter Spiegel, US managing editor at the FT, said that Biden’s decision was using “trade policy as a shield to advance economic nationalism and xenophobia” and that it “is not good policy or good geopolitics.”

As Alan Beattie, the FT’s world trade editor, noted, the US steel industry doesn’t justify this sort of over-sized reaction, and this is more about public posturing than anything else.

Iron and steel manufacture directly employs about 80,000 people in the US, 0.06 per cent of the total workforce and comfortably less than half the number of American pedicurists and manicurists. US Steel itself has just over 20,000 workers, half the number of employees at Penn State university. As I noted last week, US trade policy is disturbingly vibes-based. There’s a vague sense of the need to be seen fighting trade wars rather than actually creating jobs.

A Japanese official told Politico that they understood politics to be the driving factor behind Biden’s decision. “As long as the [US] is in a campaign, we see a huge difficulty out there…although the company is trying so hard.”

What comes next?

Biden’s denouncement came shortly after Nippon Steel formally filed paperwork with the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (Cfius). Cfius is an interagency committee, chaired by Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, that reviews inbound foreign investment for any national security implications.

The Global Business Alliance, a group that represents some of the largest multinational organizations operating in the US (companies like AstraZeneca, Sony and TSMC - but not Nippon Steel), wrote a letter to Yellen asking her to only consider the facts (ostensibly arguing the facts of the case mean the deal should sale through) and leave politics out of the decision-making process.

The ball is now in Cfius’ court. Emily Kilcrease, a Cfius expert at the Center for a New American Security think-tank told the FT that “based on past practice, it is likely that Cfius would have been on track to clear the deal, likely with some conditions related to protection of domestic steel production and related jobs.” But now that the President has come out against the transaction Cfius could be in “the uncomfortable position of having to reverse engineer their risk assessment to fit a politically determined outcome.” Especially because Cfius will have to come up with a reasonable explanation as to how Japan, arguably the US’s most important non-NATO ally and a key bulwark against China in the Pacific, represents a major national security risk.

Not to be outdone though, the Justice Department (DoJ) is also taking a look at Nippon Steel over an anti-trust issue that might surface from this deal. Politico reported that a plant in Alabama, currently owned by Nippon Steel and ArcelorMittal (a European conglomerate), competes with US Steel for business. The DoJ is worried that Nippon “would outright own one major auto supplier as well as half of another one”. The easy solution here is for Nippon Steel to sell its stake in the Alabama plant, but it isn’t going to do that if Biden shuts down Nippon Steel’s purchase of US Steel.

*****************

Investing in the US already has its challenges, including higher costs and a lot of regulatory scrutiny. We are seeing first-hand how this can directly impact investment. Just this week, a handful of foreign suppliers to TSMC and Intel, the major semiconductor firms, who are planning on building production facilities in Arizona to support a more US-based supply chain, announced delays because of labor and cost issues.

Nippon Steel is a publicly-owned corporation in Japan who’s largest shareholders are asset mangers and insurance companies. Nippon Steel is not the arm of the Japanese government. And even if it was, Japan is an ally. This idea that the Japanese government controls Nippon Steel, like the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) control Chinese state-owned enterprises is wholly inaccurate.

It’s not like China’s Baosteel (the world’s largest steel manufacturer) or Iran Steel2 is swooping in to pick up a prized US asset here. Nor is a Japanese firm looking to acquire an AI-focused firm that could have a real strategic impact. In either one of those situations, it might make sense for the deal to be heavily scrutinized by the US government as possibly going against American interests. But that’s not the case.

Even if you want to argue US Steel is important for national security purposes, the facts don’t really back it up. Depending on how you ask, the Department of Defense buys 1-3% of the total US steel industry’s product - and the most important bits are produced from plants owned by Cleveland-Cliffs. US Steel itself is not a major supplier of the US government.

Selective friendshoring when it only suits America’s ideal is not the way to encourage allies to decouple from China and invest in the United States. If the US starts rejecting investment from allies because we don’t like how it is perceived, this will serve as a reminder that our industrial policy truly is “America First”.

There is a reason the Global Business Alliance is lobbying for this deal to go through. If the US is going to be overly protectionist, and not a reliable ally, then foreign corporations are going to steer clear.

Some might think that is a good thing, keep production local and protect American jobs. But in an American industry like steel, that has slowly become less relevant, that doesn’t seem like the right approach to take. There is no proof Nippon Steel is going to move jobs out of the US, nor is the company any sort of national security threat. Earlier this week, a Nippon Steel executive reiterated Nippon Steel’s commitment to invest, not cut jobs or move production abroad.

But you already knew that.

This is all about political posturing for November. Pure and simple.

Think center-right, not MAGA.

This is a made-up company, but you get the point.

Thanks for this report….But, This is sad. The economy is global and we’re acting more and more local.