The Global North's failing of the Global South.

Inadequate responses to climate finance, the pandemic and conflict in the 21st century have laid bare our global divisions.

Defining the ‘Global South’

In a piece earlier this year, the Pearson Institute for International Economics defined the Global North and South based on GDP/capita.

All countries with 2021 GDP per capita above US$15,000 are considered part of the "Global North," with the addition of Bulgaria and Romania (GDP per capita $12,221 and $14,858, respectively) as members of the European Union. Under that definition, both Russia and Ukraine are in the Global South, as are China and India. Conversely, some geographically southern countries such as Chile and Uruguay are classified as part of the Global North under this GDP per capita criterion. Thus defined, the Global South represents 85 percent of the world's population and nearly 39 percent of global GDP.

Basically, this means the G7, Australia, New Zealand and a few oil-rich Gulf states (Qatar, Saudi Arabia) classify as the Global North, and everyone else is the Global South. This seems like a reasonable approach.

That being said, it is impossible to divide the world into two perfectly cohesive blocs. Every country is unique with its own set of values, resources and characteristics that do not fit in a neat box. So while there have been calls to get rid of the term1, for our purposes today it does the job.2

Climate finance

As we all know, the Global North is responsible for the lion’s share of historical emissions - and the corresponding climate crisis. However, the climate crisis does not recognize borders. So while the Global North was free to develop in the 19th and 20th century without a care in the world (at least regards to climate change), the Global North has been telling the developing world that this fossil fuel-dependent development path has been closed, and a new one must be devised.

But many of the worst climate impacts are felt in the developing world. One example is last year’s flooding in Pakistan, which displaced 33mn people and caused $15bn worth of damages. Pakistan’s GDP in 2021 was around $350bn, so this damage amounted to 4% of one year’s worth of GDP. Yet, Pakistan is responsible for 0.30% of cumulative historical emissions. It doesn’t take a math wiz to figure out that is unfair.

As such, there is an underlying tension over how much developed countries need to support developing countries adapt and mitigate climate change. At the 1992 UN conference in Rio, the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibility’ (CBDR) was formally adopted to indicate a shared moral responsibility to address climate change. But CBDR has been mired in difficulties, in particular how to interpret it and how to divide countries between developed (with an obligation to reduce emissions) and developing (an obligation to merely report).3

At Paris in 2015 (where the eponymous Paris Agreement was agreed), countries agreed to nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to self-identify climate pledges to pursue the global goal of staying below 2°C of warming (ideally 1.5°C). This would allow each country to take into account its unique circumstances and resources to devise an achievable goal. But many of these have not been pursued with adequate speed or are not strong enough.

A failed commitment

To help developing countries finance their climate efforts, the developed countries agreed at the 15th UN Conference of Parties (COP15) in 2009 to mobilize $100bn/year by 2020. However, as the chart below demonstrates, these countries came up short of this goal.

Breaking down the $100bn based on historical emissions, the Overseas Development Institute finds that some countries like France and Japan contributed more than their fair share to the fund while others fell woefully short of their target (shocking, I know, that the US came in last despite being most responsible…the US provided $2bn of a projected $43bn).4

On top of this, an Oxfam investigation this year determined that of the $83bn mobilized in 2020, only $25bn has actually been spent. As the report outlines,

The $83.3 billion claim is an overestimate because it includes projects where the climate objective has been overstated or as loans cited at their face value.

By providing loans rather than grants, these funds are even potentially harming rather than helping local communities, as they add to the debt burdens of already heavily indebted countries —even more so in this time of rising interest rates.

A 2022 report by the Climate Policy Initiative found that 76% of climate finance stays in the country of origin; predominantly China, North America and Western Europe. So despite close to a billion people in Africa having limited-to-no access to electricity, the continent has seen only 2% of global renewable energy investment. And if these nations are lucky enough to receive funding, it is usually in the form of a high-interest-rate loan, and therefore more expensive than the same investment in the less-risky Global North.

Yes, the Global North contributes to multilateral institutions like the World Bank and IMF who finance climate change projects. But if you are going to promise to mobilize a set amount of money for an explicit goal and fail, that is going to have ramifications.

Loss and damage fund

At COP27 last year in Egypt, there was a tentative agreement reached for a ‘loss and damage’ fund. After many debates and all-nighters, delegates from around 200 countries agreed to set up a fund to support “particularly vulnerable” countries suffering from climate change. This would be separate from adaptation and mitigation funds - this fund would compensate nations for losses already experienced. This has been coined by some as “climate reparations”, though US Envoy John Kerry has been quick to denounce this claim (because there is no chance Congress would allow America to pay reparations to other countries).

However, this appears to have been fool’s gold. Critically, the negotiators only reached an understanding; the actual terms, conditions and structure of the fund would be negotiated over the next year in time for the upcoming COP28 in Dubai. Despite, in the words of John Kerry, the developed countries’ “moral obligation” to help offset the developing countries’ losses, the rich countries wanted the funds to flow through existing structures like the World Bank and IMF.

Last week, the agreement over a loss and damage fund between the rich and developing nations broke down. The dispute is over where it is located (the developed countries want the World Bank to play a key role, the developing do not trust the World Bank) and how it will be funded (if the fund has no capital, it can’t do anything!). The US has argued China and Saudi Arabia should play a more substantive role in financing the fund, something these countries disagree with.

Citizens in developing countries though don’t care about the nuances behind who is responsible for financing the fund. They want help, and right now, they aren’t getting any.

Covid response

Government spending

One of the most visible examples of the Global North neglecting the Global South in recent years was in response to the pandemic.

While governments in the Global North spent previously unimaginable sums of money to protect their citizens (rightly, I might add) and closed borders, the Global South was left to their own devices. And the Global South’s coffers are not nearly as plentiful. To support widespread vaccination programs, high-income countries had to increase their health spending by less than 1%. Conversely, for low-income countries to hit 70% coverage, they have to increase their health care spending by 56%.

After years of post-Global Financial Crisis austerity, the European Union stepped up and agreed on a €750 billion aid package for the bloc in summer 2020. By June 2021, the United States, across two separate administrations, had authorized around $6tn for Covid relief.

On the other hand, the lowest-income countries lost around $150bn in 2020, approximately 2019’s development assistance. To counter the impacts of the pandemic, low-income countries could only spend less than 2% of GDP in 2020, while advanced economies could spend 8% (of their collectively much larger GDP).

And going beyond health spending, this filtered down to education. While no one in the Global North was happy with Zoom school, at least its was an available option. On average in 2020, kids in advanced economies lost 15 days of instruction, compared to 70 in low-income developing countries.

Vaccine inequity

When the medical miracle mRNA vaccines were quickly introduced 9 months after the WHO’s pandemic declaration, the hope was that vaccines could be shared globally. However, this was not to be the case.

In January 2021, during the early days of the vaccine rollout, when 80mn doses had been distributed globally, only 55 total had gone to low-income countries (they all went to Guinea). In May 2021, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the leader of the World Health Organization, described the situation as a “vaccine apartheid.”

As the rollout progressed, the situation did not get much better. By the end of August 2021, over 50% of people in high-income countries were fully vaccinated. At the same time, only 1% were fully vaccinated in low-income countries. As you can see from the chart below, the divide in 2023 is still clear as day.

And then, as the Omicron variant hit, high-income countries started rolling out boosters while the overwhelming majority of people in low-income countries had not received one shot.

Vaccine coverage as at November 2021

Part of this inequity was the protectionist attitude of drug companies, like Pfizer, seeking to preserve their proprietary formulas and sky-high profits. But governments also were acting irresponsibly, building up vaccine stockpiles that their citizens were never going to fully utilize. Doctors Without Borders noted in October 2021 that high-income countries had 870mn excess doses, 500mn in the US alone, that could have been redistributed to the rest of the world. Hoarding amplified the Global South’s discontent with the Global North, and meant that even when doses did arrive, citizens were suspicious that they might be defective if Americans or Europeans did not want them.

As a result, people across the Global South died unnecessarily. In an open letter signed by political figures and activists from around the world marking the third anniversary of the WHO’s declaration of Covid-19 as a pandemic, this group notes that had the vaccine been more equitably distributed, “at least 1.3mn lives could have saved in the first year of the vaccine rollout alone, or one preventable death every 24 seconds.”

Even now, vaccine hesitancy remains a major problem in Africa, exacerbated by social media misinformation and supply chain logistical issues. Part of these problems could be alleviated with better targeted spending. However, as we previously saw, this is not a sustainable solution for much of the region.

Colonial hypocrisy

Russia/Ukraine

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 further exposed the gap between the Global North and the Global South. While the Global North was outraged by Putin’s disregard for territorial sovereignty and liberal values, the Global South has placed more value on the practical implications of the invasion - specifically the impact on food security and inflation.

Ukraine is known as “Europe’s bread basket” for a reason - it is one of the largest global exporters of sunflower oil, barley, maize and wheat. And from 2016-2021, Asian and African countries received 92% of Ukraine’s wheat export. Following Russia’s invasion, food shortages coupled with ongoing inflation to push prices to record levels. This means countries like Egypt, that previously relied on food exports from Ukraine, all of a sudden faced a crisis it was ill-prepared to respond to.

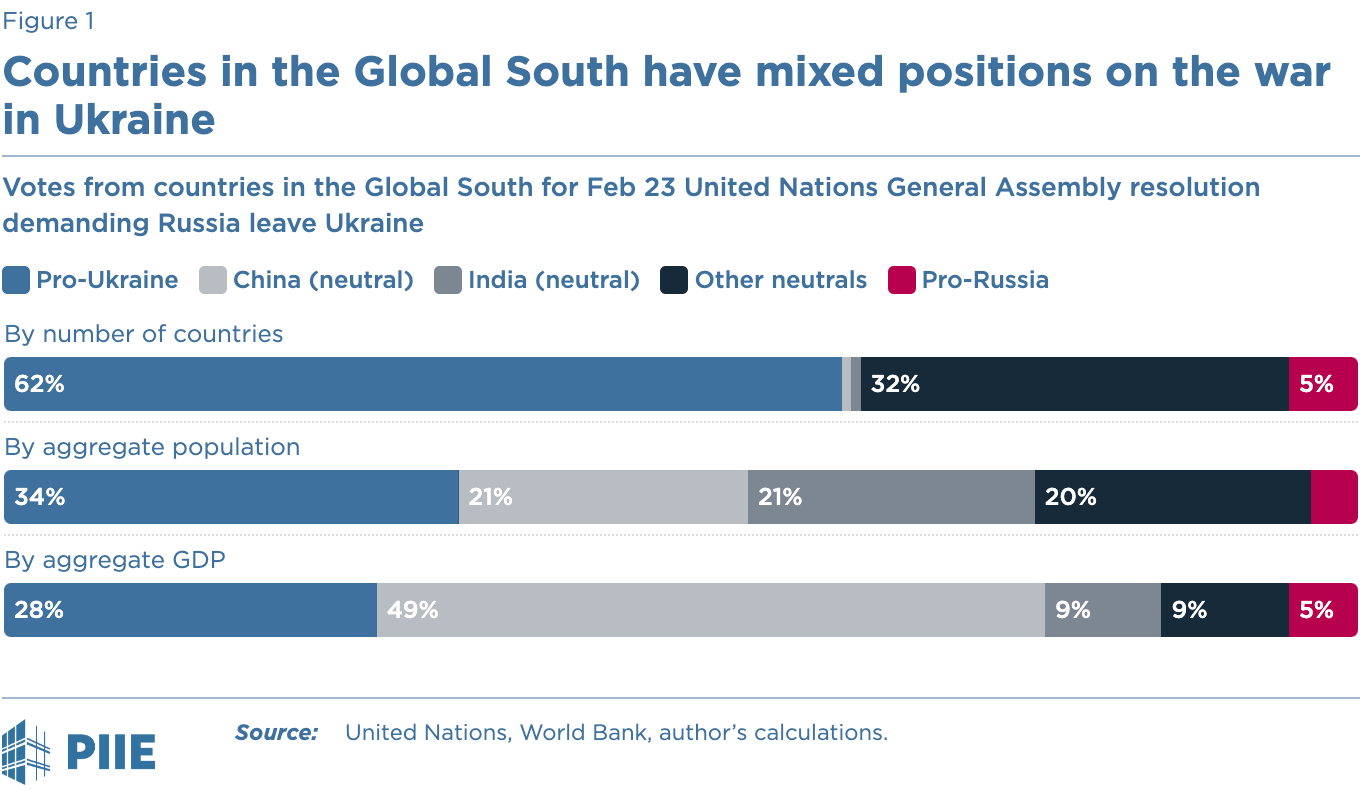

You would think that since these food shortages were the direct result of Putin’s invasion, the Global South would stand with the Global North. The reality is more nuanced. Russia engaged in a propaganda campaign across the Global South to try and pin the blame on the west and the US as the imperial powers.5 Whether or not Russia’s propaganda campaign was a success is debatable. Generally speaking, the Global South has not been demonstrably pro-Russia. However, in UN General Assembly votes, many of these nations (including China and India) chose to stay neutral.

Voting results on the one-year anniversary of Russia’s invasion

Even though Ukraine has stated it has no interest in negotiating with Russia, this has not stopped others from proposing peace plans. Global South countries like China, Brazil and Indonesia have all tried to implement peace plans to end the war. However, these have generally been ridiculed by Ukraine and the Global North as non-starters. Ukraine’s defense minister said Indonesia’s plan - which would have created a demilitarized zone along the front lines - “sounds like a Russian plan.”

The real disconnect here is that, while the Global North will not tolerate Putin’s disregard for societal norms, the Global South wants the war to end for more practical economic reasons, and sees the Global North’s sudden embrace of norms as hypocritical when put in the wider context. Sudan has been in a state of civil war. Africa’s Sahel region has been embroiled in turmoil for years. Saudi Arabia has been at war with Houthis rebels in Yemen since 2014 (and the US has provided arms to the Saudis). But when Ukraine got invaded, the US and Europe ramped up their foreign assistance packages and aid was diverted to support the Ukrainian war effort.

Beyond the practical implications, another, more deep-rooted, reason for these different perspectives stems from our different histories with colonialism. As one East African correspondent noted immediately after Putin’s invasion,

[O]ur national histories…make it hard for us to see Russia as the ‘bad guy’ and Ukraine’s pursuit of a Western way of life – including membership of the European Union and NATO – as an innocent desire that makes all who support it the ‘good guys’.

All African countries (apart from Ethiopia and Liberia) were colonised, our homes cut up and shared like cake among European powers at the Berlin Conference of 1884–85 and in later years. The result? Some of the bloodiest subjugations in human history. No African country was ever colonised by members of the former USSR.

America’s post-9/11 time in Iraq and Afghanistan is a prime example. One of George W. Bush’s public rationale’s for embarking on Operation Iraqi Freedom was to help “Iraqis achieve a united, stable and free country.” However, even in the early days of the occupation it was clear that our presence would not be welcomed.

And the subsequent impact of America’s extended occupation post-9/11 cannot be understated. Across the war zones (including Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen), around 940,000 people were killed from direct war violence related to the War on Terror. Another 3.6mn deaths can be tied to the War on Terror’s impact on the ground - including economic collapse/food insecurity, the collapse of public infrastructure, environmental damage and public trauma/violence. Millions more were displaced, and trillions of USD were spent across the years. The world then watched as, after 20 years of occupation, the US completed a chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan. This appeared to many as the US cutting its losses and abdicating further responsibility for the region, a void the Taliban was happy to fill.

And as Russia’s war crimes were broadcast throughout the world, people in the Global South were reminded of the years of US occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan, questioning why the US-led alliance had now developed a moral backbone.

*************

The Global North has recently shown signs that it understands the Global South is not fully on their side. Earlier this year, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida invited eight Global South nations to the G7 summit. French Prime Minister Emmanuel Macron hosted the Summit for a New Global Financing Pact where Barbados’s Prime Minister Mia Mottley presented a new climate financing plan.

However, we can’t expect a flip to switch over night. The Global North has made stands ostensibly on principal, and thrown copious amounts of money at problems. But these are relative luxuries for the Global North compared to the Global South. At the end of 2024, economic activity in emerging markets and low-income countries is projected to be around 5% below pre-pandemic levels. Interest rate increases in the Global North have compounded already high rates in the Global South to create unwieldy debt levels. Unsustainable debt begets lower credit ratings leading to less investment, slower growth and a worse standard of living.

We need to do better.

And I frankly agree with those calls

Throughout this piece, in addition to Global North/South, you will find reference to “low-income” and “developing world” below. Generally speaking, you can think of all of these terms as encompassing the same group of nations.

For example, where does China fall here? The Chinese Communist Party would say China is developing, pointing to GDP/capita, while the US would say China has developed and should be responsible for emissions reductions.

$2bn from the US is embarrassing. During the Global Financial Crisis, we spent $1.5tn combined on bank bailouts (Emergency Economic Stabilization Act) and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. We’ll get to how much we spent on Covid and the War on Terror in the 21st Century in a bit (spoiler alert: it’s a lot). But we can’t muster up more than $2bn for low-income countries?

And yes, some of the countries in the Global South profited from Russian sanctions. Post-invasion, countries like Turkey, the UAE and India saw their bilateral trade with Russia take off.

Great article. The Covid response variation is most compelling. We need to do better.