The history of: The Reichstag Fire

How Hitler manipulated a 'crisis' to turn Germany into a Nazi fascist state.

Doing something a bit different today.

The Reichstag building burns on the night of February 27, 1933.

In Berlin on the evening of February 27, 1933, Marinus van der Lubbe entered the Reichstag, the home of Germany’s parliament.

Marinus van der Lubbe

Disillusioned with a world trapped in the Great Depression, Van der Lubbe, a 24-year-old Dutch man who had recently left the Communist Party to become an anarchist, believed the capitalist system had to be burned to the ground. And the Reichstag, the physical embodiment of the global system in Germany, was the perfect setting to literally set the system ablaze.

Little did van der Lubbe know that his actions would be the spark, not toward revolution but rather, by which Adolf Hitler would consolidate power, setting the course for the coming decade of global death and destruction.

It is important here to take a step back and understand the situation in Germany in February 1933 that allowed the Reichstag fire to be the catalyzing event of a dictatorship.

The situation in Germany

The Nazis develop a following

After World War I, Germany was forced to sign the Treaty of Versailles, which included a loss of territory, reparations, and an admission of guilt. Throughout the 1920s, Hitler decried the terms of the Treaty, proclaiming that Germany hadn’t lost the war but rather had been stabbed in the back (by, amongst others, the Jewish people and Communists), and vowed to restore Germany to its previous heights.

This message resonated with the German electorate, especially young people and Hitler slowly developed a following. By the 1930 election, the Nazis won 18% of the vote, up from just 2.6% in 1928, making the Nazis the second largest party in the Reichstag.

The results of the 1930 federal election. The Nazis increased their standing in the Reichstag by nearly 100 seats.

By the next election, in July 1932, the Great Depression had ravaged the German economy. With around one-third of the working-age population unemployed, this was optimal recruiting ground for both the Nazis and the other main anti-establishment party — the Communists on the left.

An aside: One of the important aspects of Hitler’s rise was his desire to do so in a democratic fashion (though the Nazi’s control of the streets and use of indiscriminate violence cowed any real dissent). He didn’t want to simply take power through force, but to position the Nazis as the bulwark against Marxism and the Communists. Hitler framed the Nazis as the side of stability and economic opportunity while the Communists and Social Democrats, who he generally lumped together, represented chaos and anarchy.

This message appealed to conservatives and business people, who were otherwise worried about the the Nazi message of racism and anti-Semitism. So despite the Nazi’s extreme words and violence, Hitler slowly won over the industrialists, who had zero interest in a Communist government and the idea of collective property that was emanating from Russia at the time.

The Nazis appear to lose momentum

During the July 1932 election, the Nazi vote share doubled from 18% to 37% — the party was now the largest in the Reichstag. But this turned out to be their electoral high watermark (at least, in relatively free and fair elections). Less than six months later, in November 1932, another election was held and their vote share dropped to 33%, losing 34 seats.

Nazi vote share over time.

Indeed, the November 1932 election saw the pro-Weimar Republic parties (principally the Social Democrats and the Centre Party) also lose support. The main beneficiary? The Communists, who now had 100 seats in the Reichstag, though still well behind the Nazis and the Social Democrats.

The composition of the Reichstag after the November 1932 election.

Germany’s (semi-)parliamentary democracy

It is at this point that we must look at the German government, because the decisions here set the stage for Hitler’s ascent.

Germany’s post-WWI constitution established a parliamentary democracy (the Weimar Republic, named for the city where the constitution was created) with an elected president responsible for appointing a chancellor to preside over the legislative body (the Reichstag), which was elected via popular vote.

While the Reichstag effectively ran the government, the president could dismiss the chancellor and dissolve the chancellor’s cabinet and the Reichstag. The constitution also included a clause (Article 48) which gave the president the power to rule by decree without parliamentary consent.

The president of Germany at the time was Paul Hindenburg, an old war hero who, as an elderly man in his mid-80s, was increasingly less influential. Between 1930-1932, as the Nazis gained more seats and the Reichstag became increasingly divided, much of the governing was conducted by the German chancellor (Heinrich Bruning (1930-Jun 1932), Franz von Papen (Jun 1932-Dec 1932), and Kurt von Schleicher (Dec 1932-Jan 1933)) via decree through Article 48, with Hindenburg there simply as a figurehead signing off on the decree’s use.

The most dramatic use of Article 48 came in July 1932 when chancellor Papen invoked an emergency decree to remove the elected state government in Prussia. This action was derided as a major infringement on Prussian state rights — and set a worrying precedent that Hitler would later exploit.

Hitler is named Chancellor

In January 1933, a group of conservative elites led by former chancellor Papen (who was bitter over having recently been replaced by his rival Schleicher) decided that, with the Nazis losing vote share in the recent election and the Communists over-performing, the time had come to bring Hitler into government.

Papen and the conservatives loathed the Communists and felt they could insulate the cabinet with enough of their own members (with Papen himself vice-chancellor), that Hitler as chancellor could be controlled. Hindenburg also did not trust Hitler, but Papen and his team were able to convince Hindenburg that they would be able to control him.

Or, in Papen’s words, “Within two months we'll have pushed Hitler so far into the corner that he'll squeak.”

So on January 30, 1933, Hindenburg appointed Hitler Chancellor of Germany. This gave Hitler authority, but only two fellow Nazis were included in the cabinet, the rest were close to Papen. Hitler still needed the President and Reichstag to govern.

Germany was not yet a Nazi totalitarian state.

Papen, second from left, was supremely confident a cabinet comprised of himself and fellow conservative could control Hitler.

As future events dictate, he was wrong.

It is in this context, with Hitler in command but not yet possessing dictatorial power, that we return to the night of February 27, 1933.

What happened after the fire?

Acting alone, the partially blind van der Lubbe navigated in the darkness and set the Reichstag on fire…supposedly.

Considering the fallout from this event, conspiracy theories naturally abound over the true source of the fire. Did van der Lubbe have help? Was it actually a Nazi plot? However, dwelling on whether or not van der Lubbe was guilty or set-up is self-defeating. Regardless of the cause, it doesn’t change what happened next. Undoubtedly, Hitler would have conjured up a different crisis to amass power and establish his dictatorship.1

Hitler and other Nazi ministers arrive at the Reichstag shortly after the fire began.

Shortly after the fire started, Hitler arrived at the Reichstag and grasped the potential enormity of the situation. He immediately blamed the Communists (without any evidence), claiming this was all part of a wider Communist plot to seize the levers of power and destroy Germany. Hitler called the fire “a God-given signal. If this fire, as I believe, is the work of the Communists, then we must crush out this murderous pest with an iron fist.” Hermann Goring, one Hitler’s chief lieutenants, noted to the assembled Nazi braintrust that,

This is the beginning of the Communist Revolt, they will start their attack now! Not a moment must be lost. There will be no mercy now. Anyone who stands in our way will be cut down. The German people will not tolerate leniency. Every communist official will be shot where he is found. Everybody in league with the Communists must be arrested. There will also no longer be leniency for social democrats.

Reichstag Fire Decree (February 28, 1933)

The day after the fire, Hitler quickly convinced Hindenburg to sign the Decree for the Protection of People and State, colloquially referred to as the Reichstag Fire Decree. This expanded the government’s power to infringe on German civil liberties by suspending freedoms of speech, press, assembly2 and the protection against unlawful arrest / detention. Douglas Reed, a British writer, described the situation as follows:

When Germany awoke, a man’s home was no longer his castle. He could claim no protection from the police, he could be indefinitely detained without charges; his property could be seized and his communications over-heard.

The decree also seized on the precedent set the previous year by Papen in Prussia and gave the federal government the power to interfere in the German states.

Under the guise of restoring public safety and order, the Reichstag Fire Decree handed the Nazis legal cover to go after political opponents, most prominently Communists, without cause. Once the Decree was issued, Nazi stormtroopers and police were mobilized and, working off already-written lists of collaborators, arrested thousands of Communists and Social Democrats within hours. Communist publications and meetings were also banned.

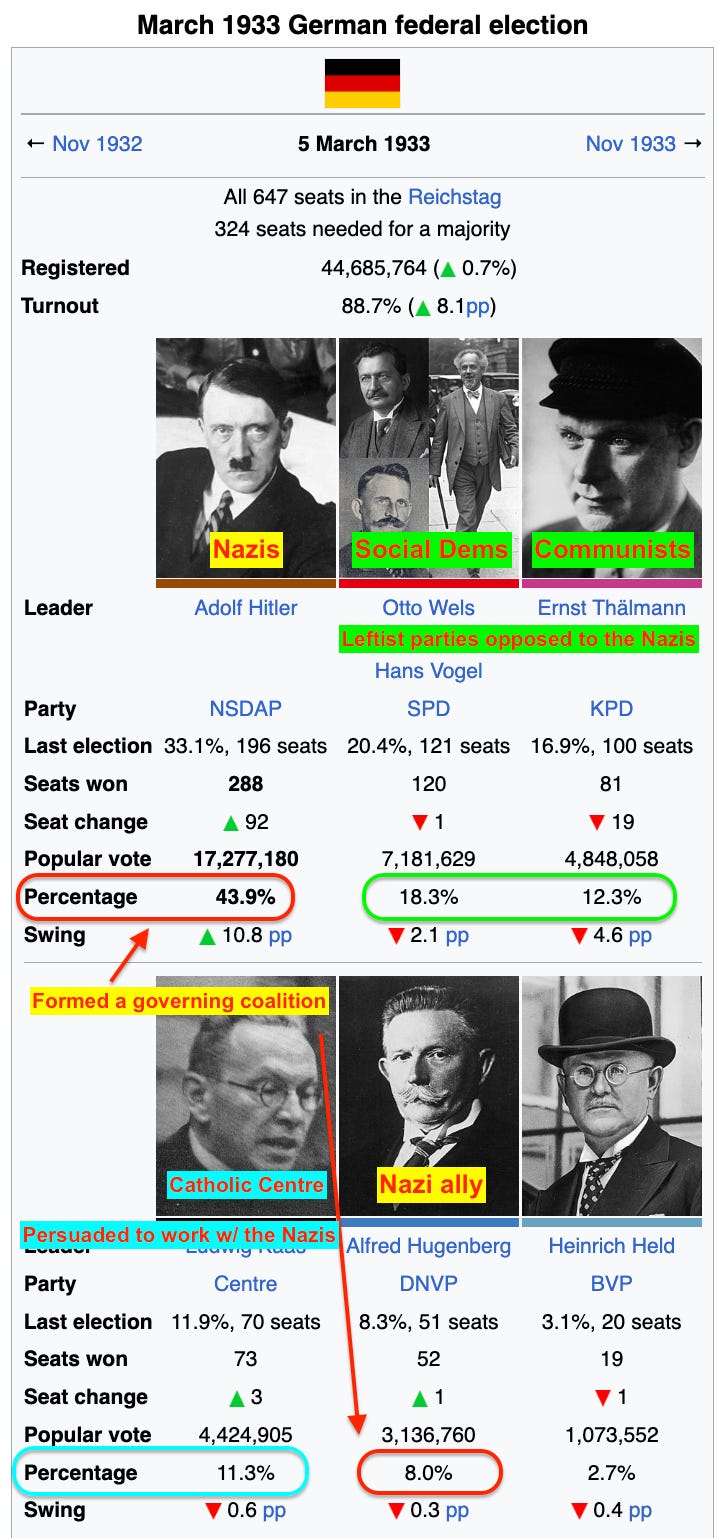

March 5, 1933: Another round of elections

About a week after the fire (March 5, 1933), another election was held. Hitler wanted an election to finally secure a Nazi Reichstag majority and to grant his chancellorship a veneer of democratic legitimacy. Remember, he had been appointed chancellor only after Papen’s political maneuvering. Now, Hitler sought a Nazi electoral victory to certify his rule in the eyes of the German public and broader international community.

Hitler also wanted to do away with the parliamentary democracy of the Weimar Republic and establish a dictatorship, with himself as dictator. But as noted above, he wanted to do so through the democratic process, which meant amending the Weimar Constitution. And to change the constitution, he needed the support of a supermajority in the Reichstag, or two-thirds of the vote.

Perhaps this election would give him the votes necessary to pursue this goal.

Granted, just because the election was taking place doesn’t mean the situation on the ground was not heavily tilted toward the Nazis. With the Communists and Social Democrats under siege, and thousands of Nazi opponents already arrested, Hitler had a massive structural edge. Nazi stormtroopers and police actively engaged in street violence to intimidate voters. This election was neither free nor fair.

But while the Nazis did increase their vote share, the party still only won a plurality (44% of the vote) not an outright majority. Despite the open hostility directed toward them, the parties on the left, the Social Democrats (18%) and Communists (12%) collectively won 30% of the vote, a clear demonstration of a still sizable anti-Nazi population within Germany. Rather than secure his majority (let alone supermajority), these results forced Hitler to collaborate with the fellow right-wing German National People’s Party (DNVP, won 8% of the vote) to form a cabinet.

The Enabling Act (March 23, 1933)

Despite not having the required supermajority, three weeks after the election the Nazis introduced the Enabling Act. If passed, the Enabling Act would arrogate all power to the Reich cabinet led by the chancellor. In effect, this would give Hitler the ability to rule without any checks and render the Reichstag impotent.

After weeks of attacks and repression, most of the Communists had been arrested, and those not arrested were threatened if they tried to take their Reichstag seats, rendering their opposition moot. Hitler also struck a deal with the Catholic Centre Party that included a promise to respect the role of the Catholic Church and an assertion that the Act would only be in place for a short period of time.3

So when it came time to vote, the Social Democrats were the only party actively against the Act. During the vote in the Reichstag, as Nazi stormtroopers looked intimidatingly down on the proceedings, one man, Otto Wels, the leader of the Social Democrats, courageously spoke out against the Enabling Act and in support of democratic values.

Never before, since there has been a German Reichstag, has the control of public affairs by the elected representatives of the people been eliminated to such an extent as is happening now, and is supposed to happen even more through the new Enabling Act…we stand by the principles enshrined in [the Weimar Constitution], the principles of a state based on the rule of law, of equal rights, of social justice. In this historic hour, we German Social Democrats solemnly pledge ourselves to the principles of humanity and justice, of freedom and socialism. No Enabling Act gives you the power to destroy ideas that are eternal and indestructible.

Hitler interrupted the speech to denounce Wels, saying it did not matter what the Social Democrats did, Hitler had the votes.

Indeed, Hitler was right. In the end, the Enabling Act passed, 441-94. Only the 94 Social Democrats present at the Reichstag that day defied Hitler and voted against the Act.

With the passage of the Enabling Act, Hitler now did not need the pretext of the Reichstag or Hindenburg to govern.4

The democratic system of the Weimar Republic was over.

The era of Nazi fascism had begun.

If you are interested in learning more:

I highly recommend the work of the historian Richard Evans. His books, The Coming of the Third Reich and Hitler’s People, do a masterful job Hitler’s rise and the people that enabled it.

If you are more of a podcast person, The Rest is History has a number of series on the rise of the Nazis, the Nazis in power and the lead-up to the Second World War that are well worth seeking out, especially episode 298: The Nazis: Total Power (Part 4) which goes into further detail on the events detailed above.

If you enjoyed this edition of Nuance Matters, consider letting me know by buying me a cup of coffee!

Cheers!

Despite van der Lubbe’s apparent guilt, his conviction was reversed in 2008 by a German court in accordance with a 1998 German law that deemed Nazi-era sentences to be unlawful.

Essentially what we in the US would refer to as First Amendment Rights.

You will be unsurprised to learn Hitler reneged on these promises.

Very helpful history. Thanks for sharing. Scary….