The problem with carbon offsets, part 2

Double counting and double claiming further expose the issues around carbon offsets.

Earlier this week, I wrote a post on the basic issues with carbon offsets. If you missed that post, here is a link to it.

In this post, I go a bit deeper on issues that are not as self-evident, but have equally devastating consequences.

*************

Double counting

In the context of carbon credits, what is double counting? Joseph Romm offers a pretty good explanation of double counting in his white paper.

If I have 10 oranges and you have 10 oranges, then when I sell you those 10 oranges, you have 20 oranges, and I have zero oranges. You the buyer would never let me sell you 10 fake plastic oranges—let alone sell you 2 fake oranges and claim that I was selling you 10 real ones, which is basically how the carbon offset market operates. With real commodities, it’s caveat emptor—the buyer is motivated to ensure the quantity and quality, even if the seller is not.

But imagine you could sell negative oranges or the reduction in the number of oranges. If I eat my 10 oranges (taking me to zero) and then sell you 10 orange offsets, which you use to claim you also have zero oranges, then to the world we are each claiming we have zero oranges. But the total number of oranges between us is not zero—it is in fact clearly 10. We just double counted the reductions.

This is a big problem for carbon offsets: who gets to include the credits in their emission reduction inventory. Double counting occurs when an emissions reducing activity happens one time, but is claimed by BOTH PARTIES.

Say a project cuts emissions by 10mn tons. If the buyer of the offsets takes credit for the emissions reductions AND the seller takes credit for reducing its own emissions by 10mn tons, this is technically double counting the project’s impact. Most of the time, one project that reduced emissions by 10mn tons gets counted by both parties, making it appear like emissions were reduced by 20mn tons.

However, this is incorrect. If one party sells offsets for a project to another party, those emissions should NOT be counted by the seller.

As part of the recent COPs in Scotland and Egypt, delegates began to address this issue. The current proposed solution is to do some double-entry bookkeeping! As part of the Paris Agreement, all countries devised self-defined national climate pledges to ensure global temperature increases remained below 2C, and ideally 1.5C. These self-defined climate pledges are known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Countries can then transfer emissions reduction credits from one to another, and these are called Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs). Article 6 of the Paris Climate Agreement states that a corresponding adjustment must be booked to properly balance out the situation and avoid double counting.1

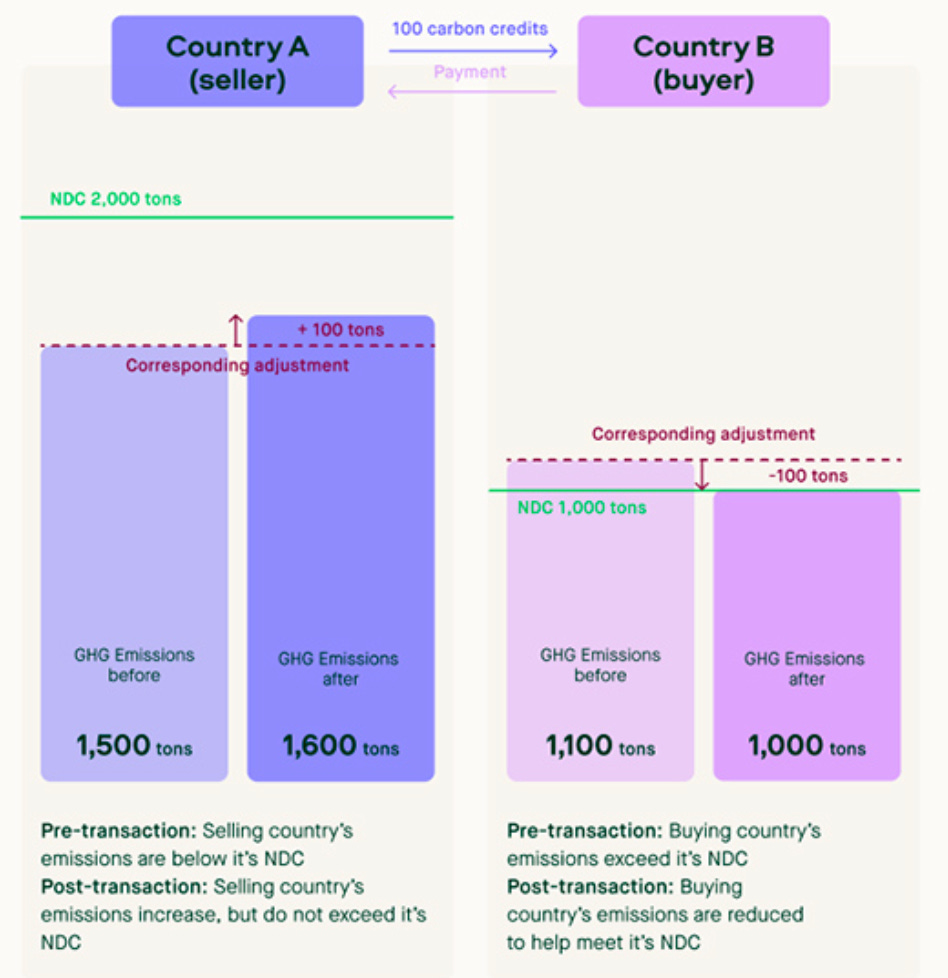

This concept is a bit confusing, so let’s use an example to help explain what this conceptually means.2

Country A has produced emissions well below its NDC of 2,000 tons of GHG emissions/year (good!), while Country B’s GHG emissions exceed its NDC of 1,000 tons/year (bad!). Since Country A has excess capacity, Country A decides to sell 100 carbon credits to Country B to reduce Country B’s emissions below its NDC.

To properly account for the transaction, the credits move from Country A to Country B, reducing Country B’s emissions by 100 tons AND increasing Country A’s counted emissions.

The AND in the previous paragraph is doing a lot of work. Both the buyer and the seller must record an adjustment to their emissions. The seller does NOT get to count the reduction as part of its pledged contribution to reducing emissions. ONLY the buyer can count these traded emissions as part of its contribution. In practice, the country selling the emissions reduction makes an addition to its emissions level, while the country acquiring the emissions reduction makes a deduction.

As Joseph Romm notes;

To be clear, at the start of the transaction, the seller has already counted the offset reductions (say 10 million tons of CO2), thereby reducing its total emissions 10 MT. Then, after the sale, it must add back those 10 MT. The seller must keep its official emissions total flat as if it never reduced its emissions in the first place.

The below chart produced by the Japanese Ministry of the Environment does a good job showing conceptually what is being done. The country on the left is performing the mitigating activity, for example installing solar panels, but then these prevented emissions in the form of offsets are purchased by the country on the right. So the country on the left has to book an adjustment to increase the amount of emissions produced, as if they never actually installed the solar panels.

Going back to the practical example of oranges,

The double counting is avoided if I tell the world I am selling my reductions (“my mitigation outcome”) to you—and so you get to subtract it from your total oranges, whereas I must add it back to my official orange total. That is, you can now say you have zero oranges (even though you actually have 10) because, from the perspective of official global accounting, I still have those 10 oranges (even though I don’t because I ate them).

Why is this important?

By committing to this transaction, the buyer makes achieving their Paris commitments easier, but the seller is making these commitments harder to reach. What countries are currently the buyers and sellers? The buyers are the rich, developed world looking purchase cheap credits to arrive at net-zero, while the sellers are the developing nations looking to grow and industrialize.

The developed countries are able to say they are arriving at net-zero with relatively weak credits while making the process of arriving at net-zero more difficult for the developing countries.

If the developing countries let the developed ones skim off their easiest emissions reductions as lower-cost authorized offsets today, then those emission reductions never officially happened. So, to achieve their own emissions targets, they would have to make up those reductions another way in the future—most likely by buying expensive authorized offsets that other developing nations will also be bidding for. That is to say, the richer countries are paying to weaken their original climate targets while shifting the burden to the poorer countries who must strengthen their original targets. That is not climate justice.

Thusly, while corresponding adjustments may help make the math more reasonable, the only serve to exacerbate existing inequalities in the global system, and ensure that achieving net zero will only be more difficult for the developing world.

Double claiming credits

Not to be confused with double counting, by which both the buyer and seller of the offsets claim the emissions credit, double claiming means that an entity sells offsets to two separate buyers who then claim the emissions reduction as part of their net zero pledge. This is facilitated by the proliferation of voluntary offset markets in conjunction with the charges under the UN-regulated Paris Agreement.

A perfect example of this can be seen in a recent deal involving Microsoft, the Danish government, and Ørsted Bioenergy & Thermal Power (ØBTP). In May, it was announced that Microsoft was purchasing credits from ØBTP for carbon sequestration work. However, at the same time, ØBTP was being paid by the Danish government for each ton of carbon that was being stored. The article discussing Microsoft’s deal said:

Orsted will be paid by the Danish government for every metric ton of CO2 that it stores, with a target to trap 430,000 tons a year. Additionally, Microsoft agreed to buy credits for 2.76 million tons of carbon removal over a period of 11 years.

As Joseph Romm noted in his white paper, (emphasis his) “this story seemed to suggest that the Danish government was buying the 430,000 tons of removal a year, but Microsoft was also buying more than half of the exact same tons.” Why should the Danish government and Microsoft both be able to purchase the same offsets if their investment is not offering any additionality and would have happened regardless? He decided to do a little bit of digging and reached out to ØBTP about this.

Ørsted confirmed in its response that the project “will capture and store approx. 430,000 tonnes of biogenic CO2 every year,” and that the Danish government has a 20-year contract to acquire those, while Microsoft “has agreed to buy credits for 2.76 million tons of carbon removal over a period of 11 years.” Ørsted explains:

Due to the funding pledged by the Danish state to help make this project a reality, the Danish state will include these removals in its national carbon accounting and in the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) of the European Union. Due to the funding pledged by Microsoft to help make this project a reality, Microsoft also plans to include these carbon removals in its own private-sector carbon accounting in support of its commitment to be carbon negative by 2030.

Both public-sector and private-sector funding was required to realize the project, and the parallel national and private-sector, non-conflicting claims to the carbon outcome are in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement and are an important component of rapidly scaling the carbon removal industry. National and corporate greenhouse gas inventories are two separate inventory systems – just as fossil emissions count in both systems today.

The response seems to indicate that both sets of funding were needed to realize the project’s emissions-cutting ambitions. However, the offsets are generated from the exact same CO2 captured. Yes, the national inventory system used by the Danish government is a different inventory system from the voluntary market used by Microsoft. But at the end of the day, the emissions are the exact same. And ØBTP already sold these to the Danish government, so it appears that Microsoft’s claims are a PR exercise.

Romm reached out to Microsoft to ask about them about this, explaining that the voluntary markets were moving towards calling these “contribution claims” or “impact claims”. This would mean that Microsoft could indicate they were investing to help Orsted capture carbon, but that they should not be offsetting these against the company’s emissions. He got no response.

While not explicitly prohibited by the Paris Agreement yet, this sort of arrangement is ripe for greenwashing - allowing companies or countries to claim credit for reducing emissions when the reality is that they were not as responsible as they would have you think. As I have previously discussed, the anti-greenwashing campaign has really picked up steam recently, and companies would be wise to avoid making this mistake.

Cost

Offsets being inexpensive is not inherent to their nature. “As a general rule, the lower the price, the lower and more dubious the quality,” noted Michael Sheldrick, cofounder and policy chief at Global Citizen, in Forbes in November 2022. In explaining “how worthless a lot of” offsets are, Stefan Reichelstein, Stanford Business professor emeritus of accounting, said in 2022, “Believe me, you can’t really eliminate a ton of carbon for $3.” Offsets are very low cost now because the large majority, as Dr. Haya and others have said, are not real or are significantly overcounted—or both.

The Wold Bank recently performed an analysis that found the cost of authorized offsets would likely exceed $100/ton for developed nations. However, as more of the problems with offsets have come to light, their price in the voluntary market has consistently dropped.

The picture below represents the costs of offsetting a round-trip flight from Newark to London. The system calculated that I am responsible for 714kg of CO2-equivalent emissions, and to offset these I would need to pay around $10 (7.78 GBP *1.27 exchange rate).

That implies that one kg of emissions is equivalent to $0.01 ($10/714kg).

The current price on the EU ETS for a ton of carbon is ~88 Euros, or ~$96. There are 1,016.05kg per imperial ton. So $96/1,016.05kg = $0.09 per kg of carbon.

The cost to offset my one-way ticket if regulated under the EU ETS scheme would be $67 ($0.09*713.73kg).

The regulated price of carbon is ~7x higher than the price I would have to pay to “offset” my flight.3

Why has the price of offsets been so low? One of the issues is that there is an overabundance of offsets that were generated years ago, when standards were non-existent, that no one purchased. Another is that, as I noted in my previous post, most of the offsets generated now are poor quality, not taking into account a proper baseline, leakage or additionality.

Historically, the seller has not been incentivized to generate high quality offsets or credits because the seller would get paid regardless of quality. At the same time, the buyer didn’t care because they got to purchase offsets at a low price that contributed to their net-zero goal. High-quality offsets cost more and come from projects that generate fewer credits (since they take into account a proper baseline, leakage and additionality), thus hurting both parties.

Analysts predict that the price for credits in the EU ETS will be around €102 by 2025, but jump to €144 by 2030. This is a sharp contrast to what is going on in the UK’s carbon trading scheme, where the government recently announced it would be offering more carbon allowances that anticipated. As a result, the carbon price in the UK dropped and is now markedly discounted compared to the EU.

On top of all of that, a cheaper price of carbon lowers the cost of energy for consumers and heavy industries, making it harder to justify spending money on renewable energy projects. This just perpetuates the cycle of emission-producing activities generating low quality emissions sold on the cheap to buyers eager to promote their net-zero achievements.

*****

As we have seen, quality offsets are expensive. And if sellers of quality offsets have to make a corresponding adjustment to their emissions balance, basically implying that they did not actually reduce their emissions, the cost of meeting the nationally determined contributions increases. As Romm puts it

Authorized offsets increase the cost to a seller of meeting its NDC. So why would developing countries sellers want to increase that burden even more by adopting an ambitious NDC to start with? As Pedro Moura Costa explained in March 2022, “in essence, host countries are disincentivised to adopt ambitious NDCs.” And so this yet another threat that offsets pose to the Paris agreement.

In a net-zero world, every country needs to get credit for reducing emissions to zero. Developing countries selling their offsets to developed countries makes it all the more difficult for them to achieve net-zero, so what would be the point? Sure, they can get money from the developed countries that they can invest into their local markets, but then they need to either (1) purchase more expensive offsets from other countries, perpetuating the cycle, or (2) eliminate emissions while industrializing, something that notably has not been achieved anywhere in the world (see the US, Europe, China, India, etc.).

Remember, climate change is a global problem. One country or company achieving net zero means nothing if the result is the rest of the world falling behind.

The reality is, these nations should not sell their emission reductions. And offsets are not a sufficient solution to climate change.

This is very similar to the practice of double-entry bookkeeping used by accountants. At the end of the day, the balance sheet has to balance and all transactions should net to zero.

Note that this has not been finalized, but based on the momentum of the previous COPs, it appears that this is the direction the world is heading towards.

Interestingly, the cost to fully replace the fuel with sustainable aviation fuel is more expensive at 136 GBP.

Double-entry bookkeeping for the win!! Really interesting stuff...

Very thoughtful piece.